>>> NOTE:

IN THE FOLLOWING, FOR EACH CHAPTER SELECTED TEXTS OR TABLES OR FIGURES ARE PROVIDED.

THEY ARE BASED ON MY LECTURES IN MELBOURNE/AUSTRALIA (2006) AND FRIBOURG/SWITZERLAND (2004).

Only after my stay in

Innsbruck I learned that a student committee

had produced and distributed a

scriptum about my lectures, to be used (illegally) in the final exam.

I had not been informed about

this text, and thus did not authorize it.

This scriptum may be

well-meant - but unfortunately it contains several significant errors.

I strictly advice not to use

it for information about my Innsbruck lectures.

1 DER BEGRIFF UMWELT

Inhalt:

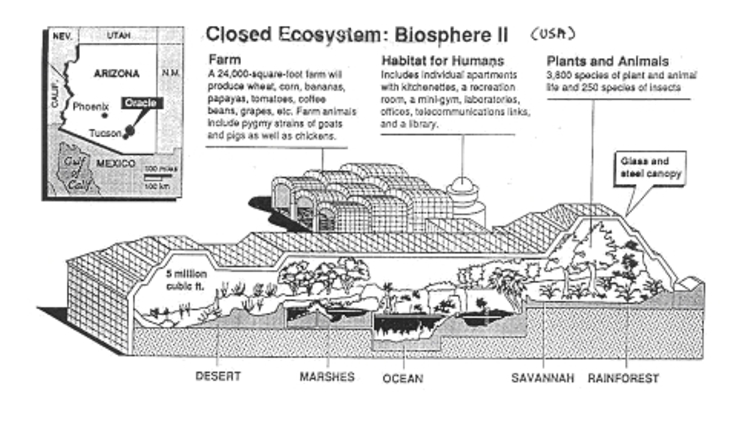

1.0 Übersicht

1.1 Begriffsentwicklung und Definitionen

1.2 Arten und Bereiche von Umwelt

1.3 Lese-Tips

Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

natuerliche \ ¦

physische < > Objekte oder Emissionen ¦ Wohn-U

/ gebaute / ¦ Arbeits-U

Umwelt ¦ Verkehrs-U

\ Individuen (Nachbarn) ¦ Freizeit-U

soziale < ¦ Versorgungs-U

Gruppe/Masse ¦

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Lese-Tips

{{ folgen spaeter }}

2 GEGENSTANDSBESTIMMUNG UMWELT-/ÖKO-PSY

Inhalt:

2.0 Übersicht

2.1 Etiketten und Definitionen

2.2 Forschungsfelder

2.3 Geschichte der Ökopsychologie

2.4 Interdisziplinäre Bezüge

2.5 Lese-Tips

Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

Lese-Tips

{{ folgen spaeter }}

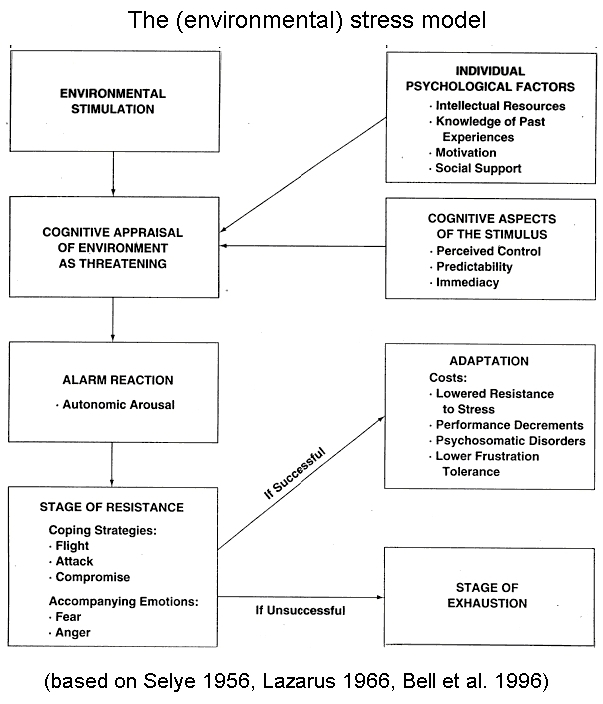

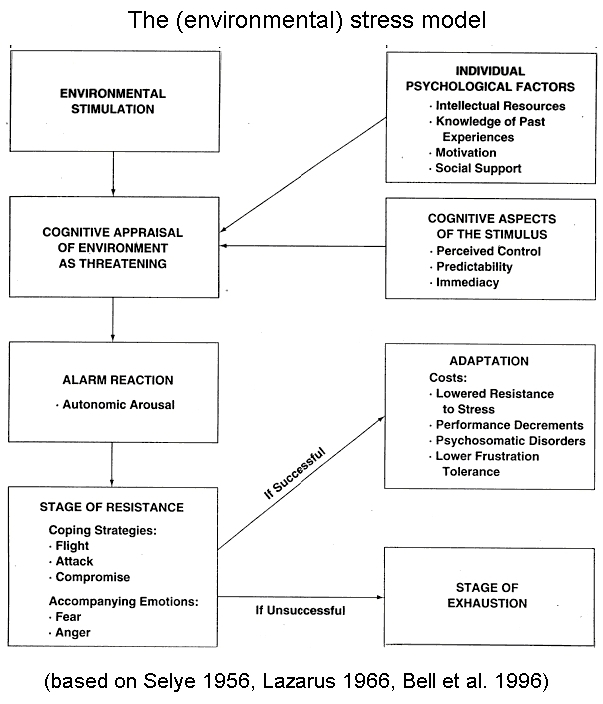

3 ÖKOPSYCHOLOGISCHE PERSPEKTIVEN

Inhalt:

3.0 Übersicht

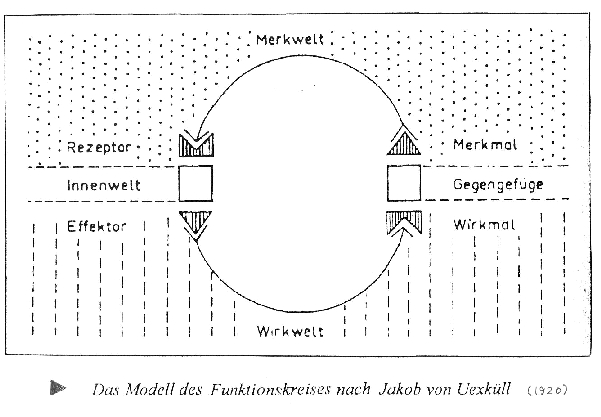

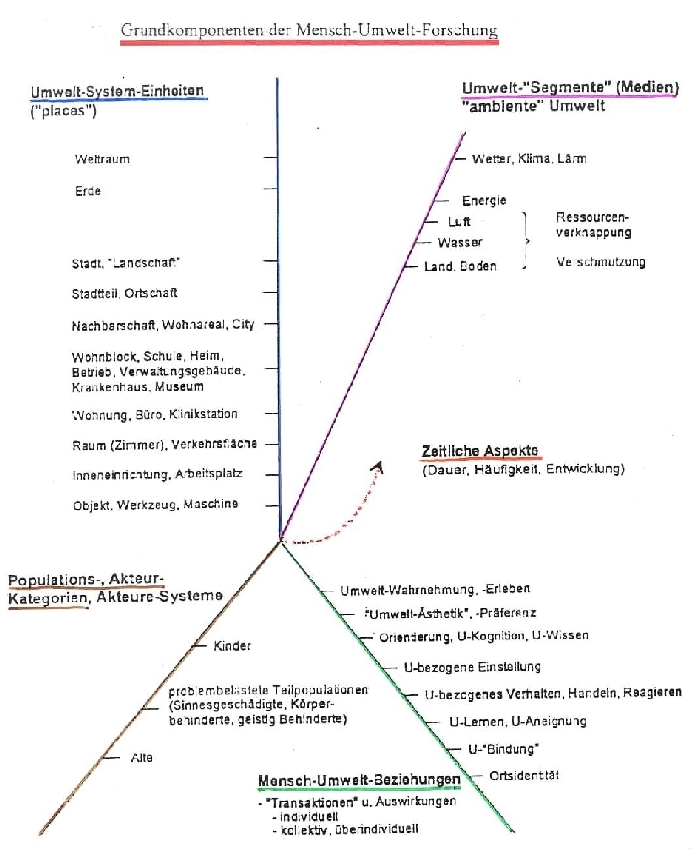

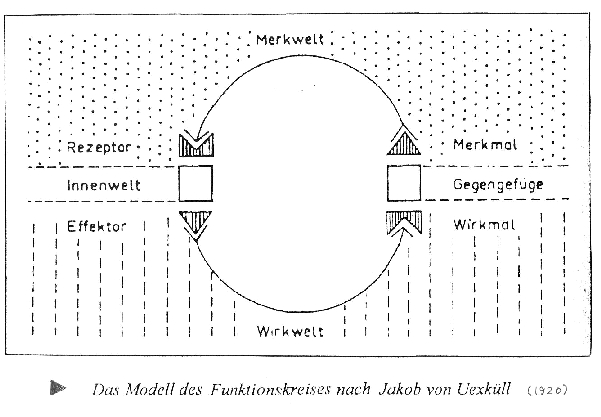

3.1 Ökologische Grundbegriffe

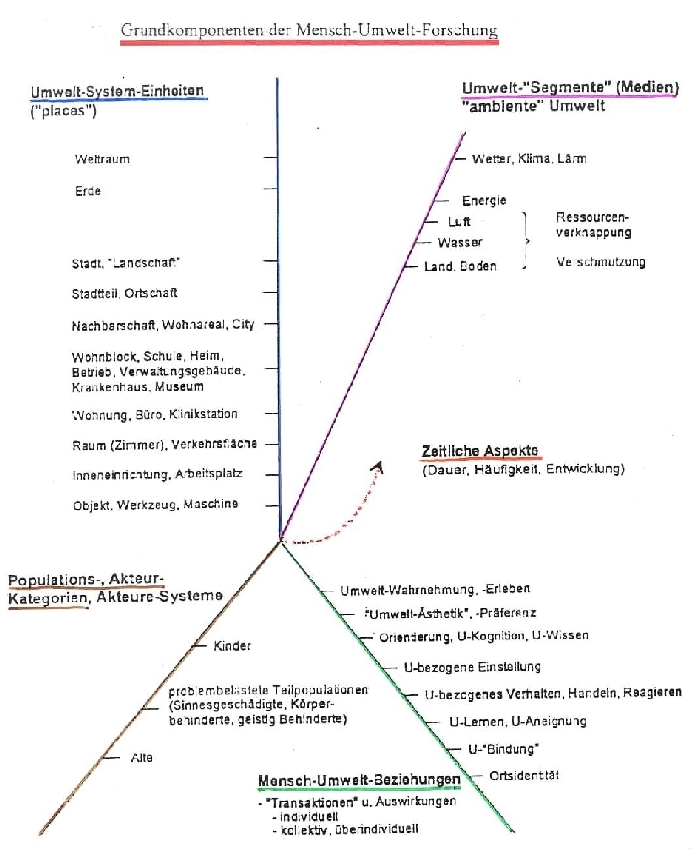

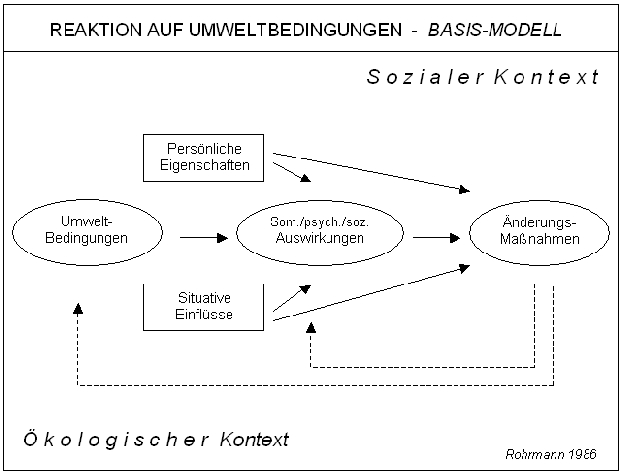

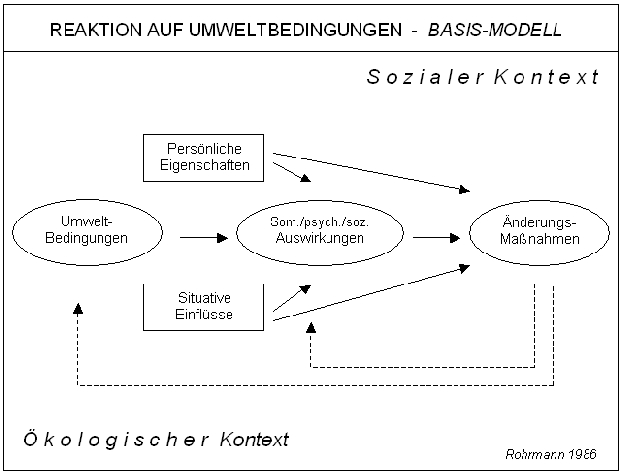

3.2 Mensch-Umwelt-Interaktionsmodelle

3.3 Theoretische Ansätze

3.4 Lese-Tips

Einige Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

{{ folgen spaeter }}

4 UMWELTKOGNITIONEN

Inhalt:

4.0 Übersicht

4.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

4.2 Orientierung in der Umwelt

4.3 Ästhetische Empfindungen

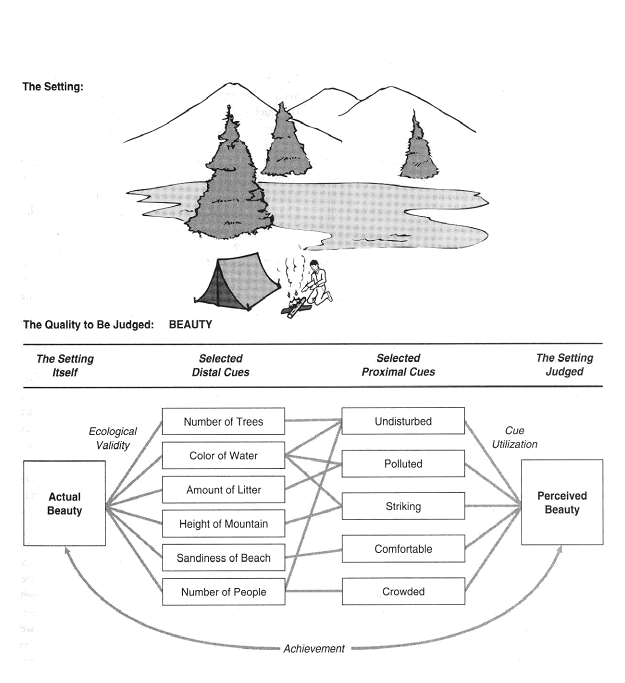

4.4 Bewertung der Umweltqualität

4.5 Lese-Tips

Einige Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

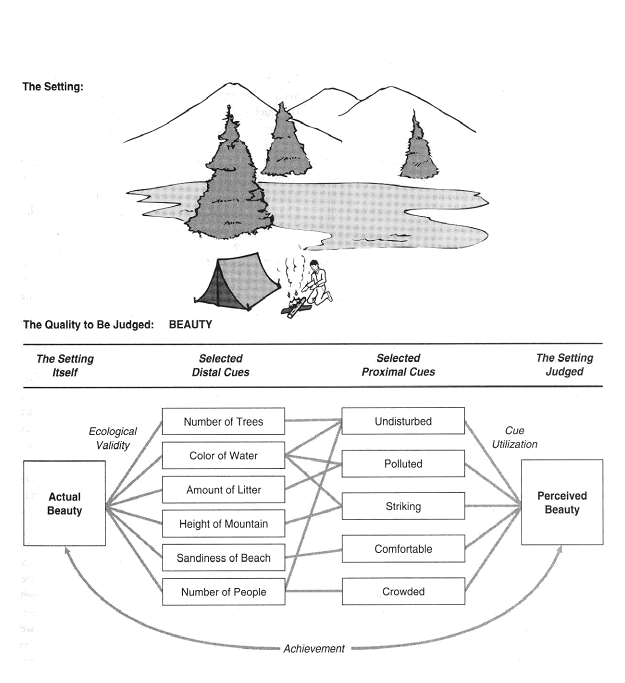

BRUNSWIK'S "LENS MODEL" OF ENVIRONMENTAL PERCEPTION

EIN TEXT ZUR "MOND-ILLUSION

Moon sliver, wider than a mile - Why does the moon appear different sizes?

By Sandra Blaksee <New York Times>

One of the most familiar illusions embraced by the human brain has finally been solved, say a father-son pair of scientists who were armed with a contraption than projects fake moons onto the sky.

In the "moon illusion", the moon rising or setting over the horizon appears much bigger than the moon directly overhead, even though both of the moons are the same size. By allowing viewers to move simulated moons towards and away from each other, the scientists demonstrate that the so-called moon illusion seems to be caused by the brain's inability to estimate huge distances in the empty night sky. The brain has many similar perceptual difficulties, they said, which produce a variety of convincing optical illusions.

An article explaining the moon illusion appears in the 4 January issue of Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, written by Dr. Lloyd Kaufman, a professor emeritus of psychology from New York University, and Dr. James Kaufman, a physicist at IMB's Almaden Research Centre in San Jose, California.

The Kaufmans said the moon illusion had baffled scientists since antiquity. Aristotle, Ptolemy, Leonardo da Vinci, Johannes Kepler, Rene Descartes and many others had tried to explain it. But now, scientists are able to take advantage of modern insights into the nature of human perception. After an image falls on the retina, where it resembles the image on a camera lens, it is sent into the brain for further processing. Within the brain's serpentine circuitry, every two-dimensional image is converted into a richer, more accurate three-dimensional representation of the world. It was within these many processing steps that illusions were born, the scientists said.

"If you look at a photograph of a person stretched out in front of you on the grass, you see enormous feet and a tiny head," Dr. Lloyd Kaufman said. But the brain took that same image and made all sorts of so-called size constancy corrections so that the person did not look distorted. The visual "fact" that the person's body was not misshapen was actually an illusion. Given the understanding that the human brain constantly deals in illusions, two theories have emerged to explain the moon illusion. They are based on opposing views of how the perceptual system computes size and distance.

One theory attributes the moon illusion to how the brain deals with the apparent size of distant objects. Because of how the light falls on the retina, and other details, the brain judges the moon to be smaller than it really is, and thus father away, when it is viewed in empty space.

The second theory holds that the moon illusion arises from how the brain deals with apparent distance not size. When people view the moon on the horizon, the story goes, their brains use myriad signals from foreground terrain to compute the moon's size. Even in flat terrain, the horizon appears very far away, so any large object seen there, like a mountain must be enormous.

Thus the moon is treated like a mountain - Huge and very far away. But when people look straight up at the moon, they no longer have land clues to compute distances. Their brains- and not their eyes - fail to adjust to the enormous distance involved and perceive the moon as being closer and closer as it rises into the night sky. The brain interprets this apparent distance discrepancy to mean that the overhead moon is much smaller than it is.

To find out which theory is correct, the Kaufmans invented a way to measure how people perceive distances to the moon. Virtually all other experiments had dealt with how people perceived the size of the moon, the Kaufmans said.

Their device consists of a laptop computer, a mirror and two lenses that can project luminous discs, or simulated moons, into the cloudless daytime sky. The apparatus works like a stereogram. Double images are directed into each eye, where they fuse somewhere inside the brain, giving the illusion of depth.

Dr Lloyd Kaufman took five people to a hillside and had them look through the apparatus until they saw two identical moons side by side. One was a fixed moon that they could hold steady. The other was a reference moon that they could move forward and back in space. People were asked to position the reference moon so it was halfway between themselves and fixed moon, the Kaufmans said.

When moving the reference moon in relation to a fixed moon on the horizon, people place the reference moon about 33 metres from themselves, the scientists said. But, when they moved the reference moon in relation to an overhead moon, they placed it only eight metres away. Thus, the "halfway" point to a horizon moon was four times father away than the halfway point to an overhead moon.

In a second experiment, subjects looked at two moons projected high overhead and pressing a key, moved one closer to themselves. They were startled to find that as the moving moon got closer, it always appeared to be getting smaller and smaller, not bigger.

The two experiments confirm the second theory, the Kaufmans said. If the brain were attending to size, the closer-in moon should appear larger, but it did not.

Source: New York Times; cited from The Age, 24-01-00

TEXT ZU MOND-PHASEN UND VERHALTEN

A Recycled Cycle: Moon Phases and Behaviour

Folklore and commonly held beliefs maintain that many aspects of our behaviour are related to phases of the moon. Sexual prowess, menstrual cycles, birthrates, death rates, suicide rates, homicide rates, and hospital admission rates are among the phenomena various people claim are affected by the moon. Often, it is maintained that a full moon increases strange behaviour. Surveys of undergraduates indicate that half of them believe people behave strangely when the moon is full (Rotton & Kelly, 1995a). Other beliefs are that the tidal pulls of full and new moons influence human physiology or psychic functioning, or that the moon's perigee (closest distance to the Earth) and apogee (farthest distance from the Earth) influence us in strange ways. Indeed, the word lunacy is derived from a belief in a relationship between the moon and mental illness.

The last full moon of the previous millennium occurred on December 22, 1999, which also corresponded to its perigee, as well as to the winter solstice or shortest day in the Northern Hemisphere. In addition, the moon on that date was almost as close to the sun as it ever gets. As a result, it appeared 14% larger than at its apogee as well as 7% brighter. No particular anomalies in human behaviour were reported. But the lore says that when a similar full moon, perigee, and solstice occurred on December 20 and 21, 1866, the Sioux warrior Crazy Horse was inspired to ambush and wipe out 80 U.S. soldiers (Golden, 1999).

It is the case that lunar tides affect some marine organisms, and there is some evidence a full moon ever so slightly increases temperatures on Earth (by 0.02° K; Balling & Cerveny, 1995). From time to time, research also appears that actually gives credence to beliefs that the moon causes drastic changes in human behaviour. For example, Blackman and Catalina (1973) found that full moons were associated with an increase in the number of patients visiting a psychiatric emergency room. In another study, Lieber and Sherin (1972) reported a relationship between moon phase and homicide. Rape, robbery, and assault; burglary, larceny, and theft; and auto theft, drunkenness, disorderly conduct, and attacks on family and children have also been linked to a full moon (Tasso & Miller, 1976). At first glance, then, it would appear that science has confirmed the folklore of the ancients (see also Garzino, 1982).

Not so fast! Closer examination of the data indicates that the mysticism of the lunar cycle may be more myth than reality. Campbell (1982), Kelly, Rotton, and Culver (1985-86), and Rotton and Kelly (1985b, 1987), among others, have reviewed the available research on the topic and concluded that no firm relationship exists between any lunar variable and human behaviour (see also Byrnes & Kelly, 1992). For example, studies conducted over a period of three to five years may report a relationship between the full moon and suicide or homicide for only one of the years studied. Researchers who conclude that such a relationship exists are ignoring the fact that it does not exist for the other years, or that these behaviours are actually lower during full moons for another year. Moreover, it is consistently found that crimes increase on weekends. For some periods of the year, lunar phases may coincide with weekends. Data based on only these periods will obviously show a relationship between the moon and crime, but data based on other periods will show the opposite relationship or no relationship at all. In addition, a self-fulfilling prophecy may operate: If police believe crime increases during a full moon, they may become more vigilant at these times and thus arrest more people. Altogether, the evidence suggests that positive links between moon phases and behaviour are spurious and are attributable to mere chance probabilities in the data or to variables not considered by individual investigators. Why do these mistaken beliefs persist? Reasons include misconceptions about physical processes (Culver, Rotton, & Kelly, 1988), attitudes acquired from one's peers (Rotton, Kelly, & Elortegui, 1986), and cognitive biases, such as basing conclusions on only a few occurrences. Given the tenacity of beliefs in moon phases causing disruptive behaviour, we suspect the lunacy of it all will continue for some time!

Source: Bell, P.A., Greene, T.C., Fisher, J.D., & Baum, A. (2001).

Environmental Psychology. Orlando, FL: Harcourt .

{{ folgen spaeter }}

5 RÄUMLICHES UMWELTVERHALTEN

Inhalt:

5.0 Übersicht

5.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

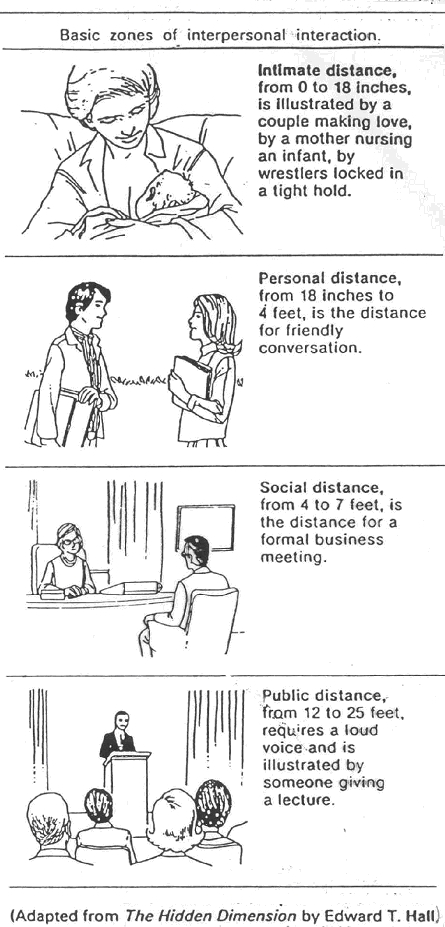

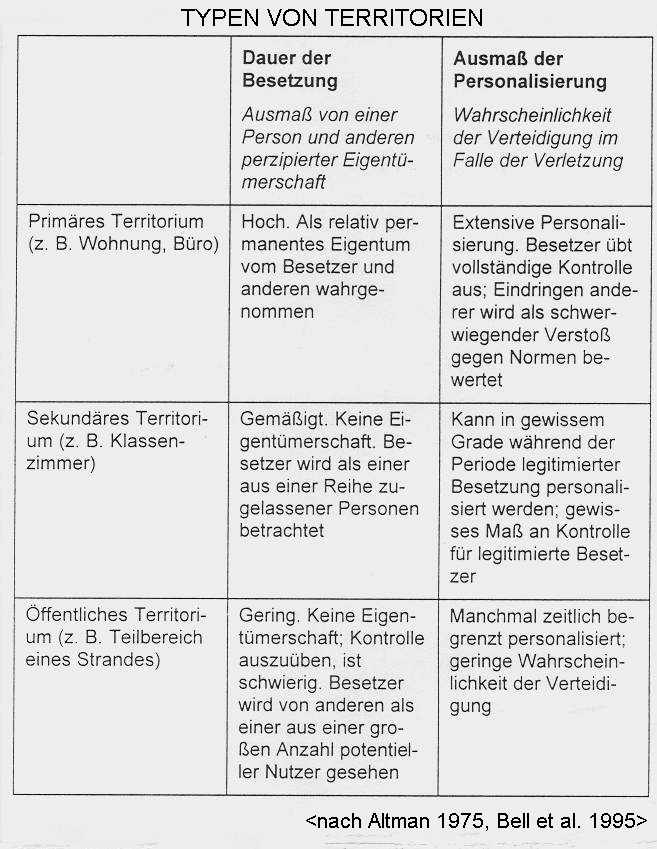

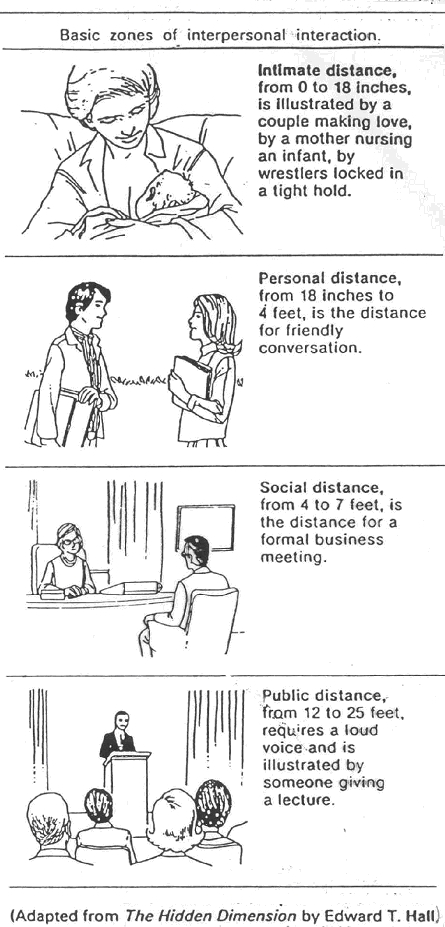

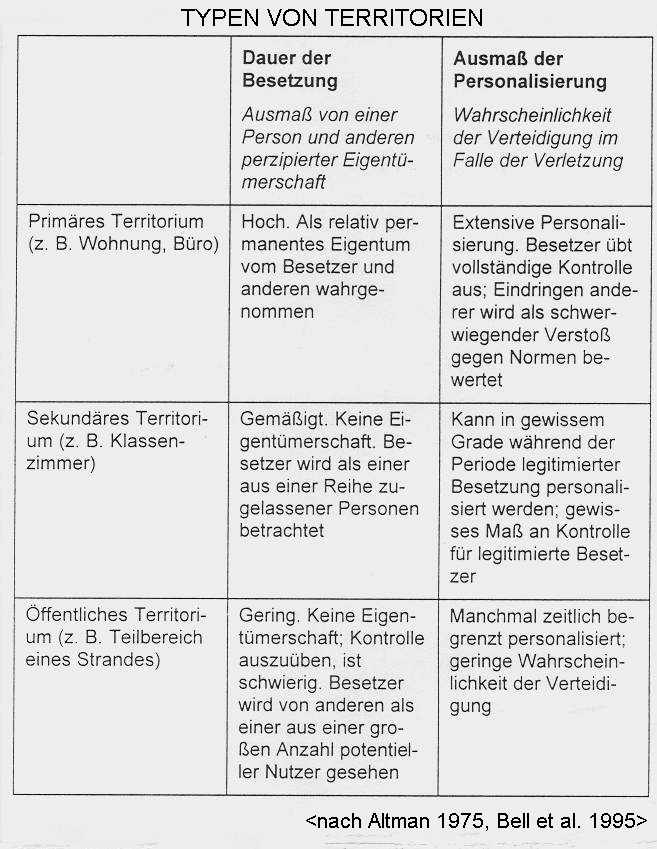

5.2 Persönliches Raum- und Distanz-Verhalten

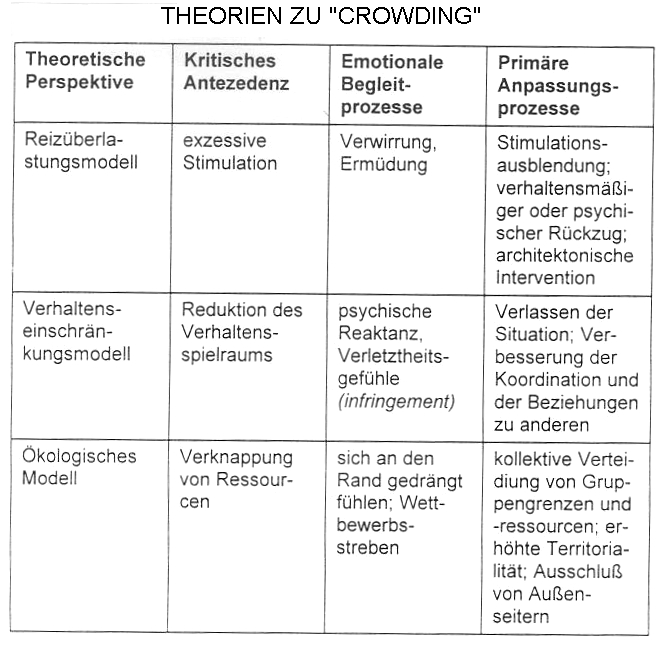

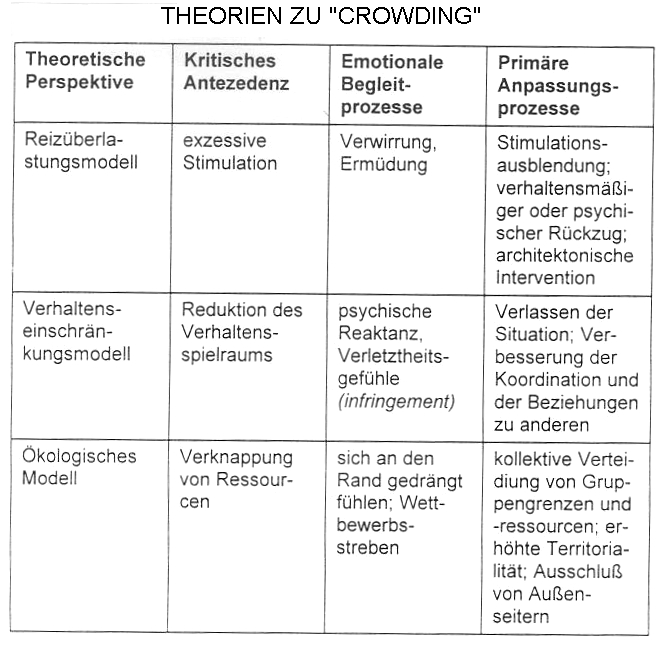

5.3 Effekte räumlicher/sozialer Dichte

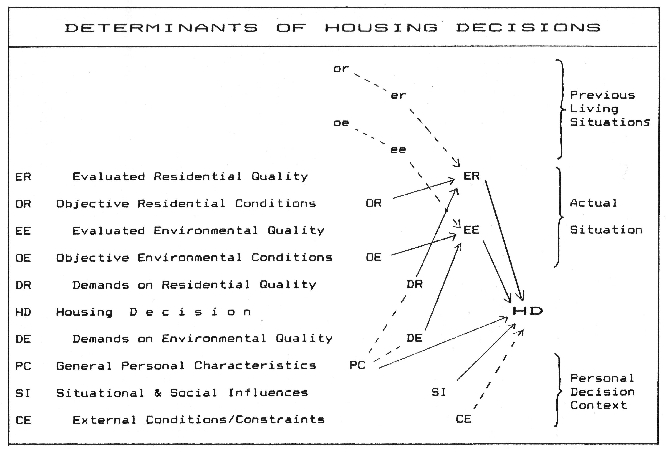

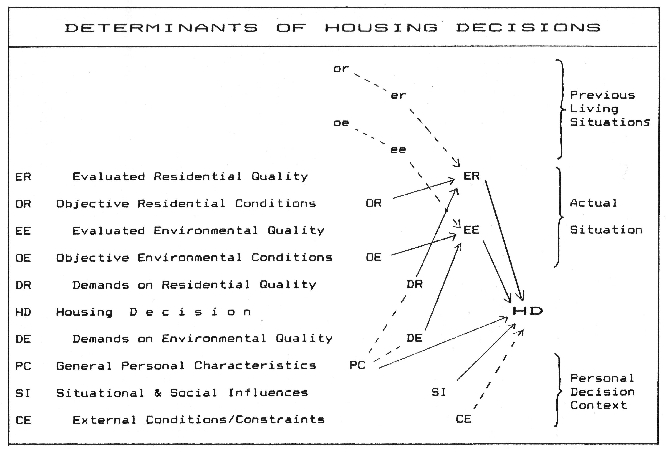

5.4 Umzugsverhalten und Wohnungswahl

5.5 Lese-Tips

Einige Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

DAS ENTSCHEIDUNGSPROBLEM "UMZUG"

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

> Entscheidungen:

o Bleiben oder Umziehen?

o {falls Umzug:} Wechsel von Wohnung/Haus/Ortsteil/Stadt/Region/Land?

> Prozesse bei der Wohnungswahl

o Suchen

o Besichtigen

o Bewerten

o Wählen

> Umziehen = räumliches Verhalten auf Makro-Ebene

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

=> Vgl. Modell in Materialien zu Kap. 9 !

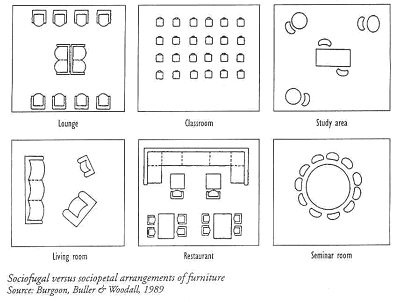

CONTACT & INTERACTION ZONES

{{ folgen spaeter }}

6 Exkurs 1: LEHRFILM "KONTAKT UND DISTANZ"

Inhalt:

6.0 Einleitung

6.1 F i l m

6.2 Diskussion

Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

:: This film was made at Frankfurt University

:: many years ago - - yet it is still instructive

:: for lectures in Environmental Psychology

Lese-Tips

Autoren: PREISER & WANNENMACHER 1980

7 NUTZUNG VON UMWELTEN

Inhalt:

7.0 Übersicht

7.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

7.2 Nutzung und Nutzbarkeit

7.3 Untersuchung von Nutzerverhalten

7.4 Lese-Tips

Eine Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

NUTZER-ZIELE, NUTZUNGSVERHALTEN, NUTZBARKEIT

Relevante Aktivitaetsbereiche

o Arbeiten o Wohnen o Erholen

Nutzerverhalten

o Sich orientieren o Aktivitäten durchführen o Umwelt verändern

Nutzbarkeits-Aspekte:

o Funktionalität o Raumbedarf o Ortswechsel

Untersuchung von Nutzerverhalten

Analyse des raum-zeitl. Verhaltens:

o Orte Zeiten o Wege

Methodik:

o Beobachten o Befragen

{{ folgen spaeter }}

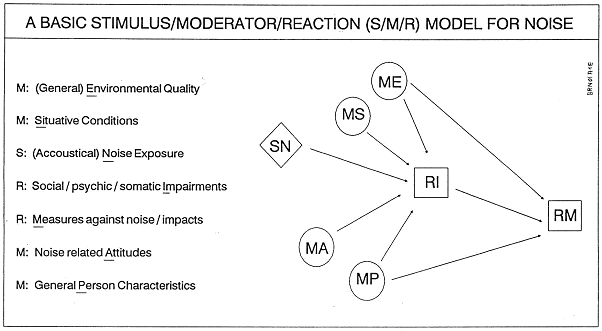

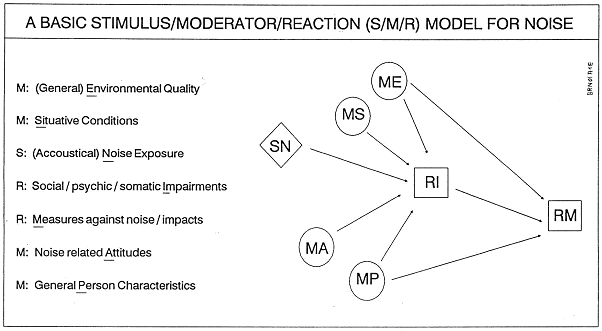

8 UMWELTSTRESSOREN UND IHRE AUSWIRKUNGEN

Inhalt:

8.0 Übersicht

8.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

8.2 Arten und Auftreten von Umweltstressoren

8.3 Beeinträchtigende Wirkungen

8.4 Bevölkerungsreaktionen

8.5 Minderungsmaßnahmen

8.6 Lese-Tips

Einige Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

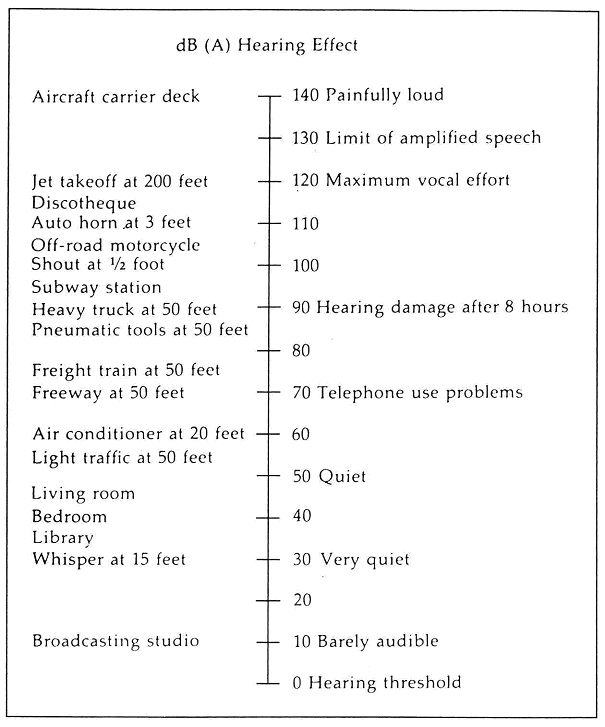

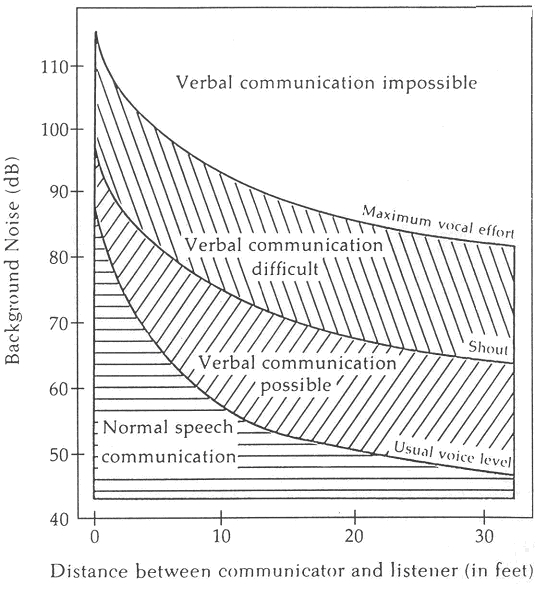

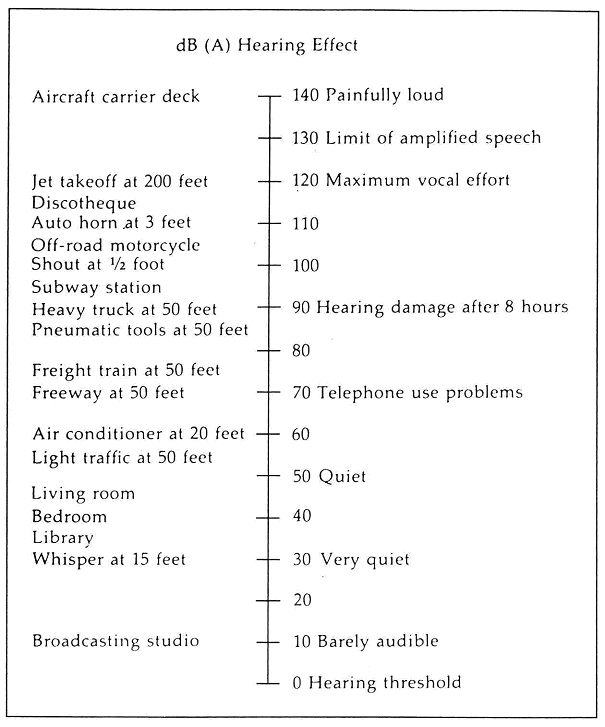

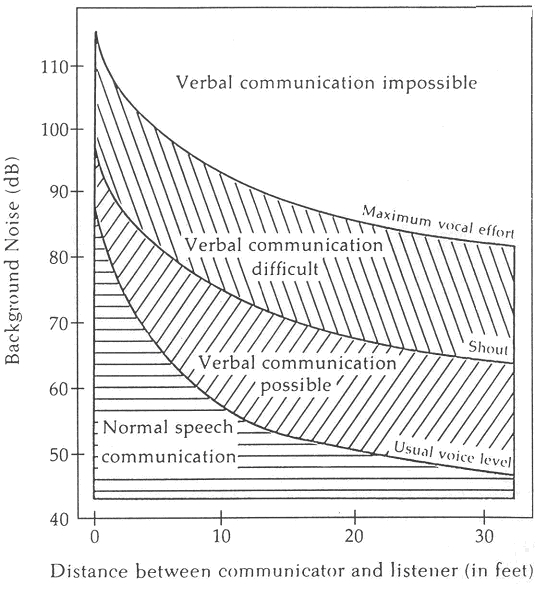

DECIBEL[A] SCALE AND NOISE EXAMPLES

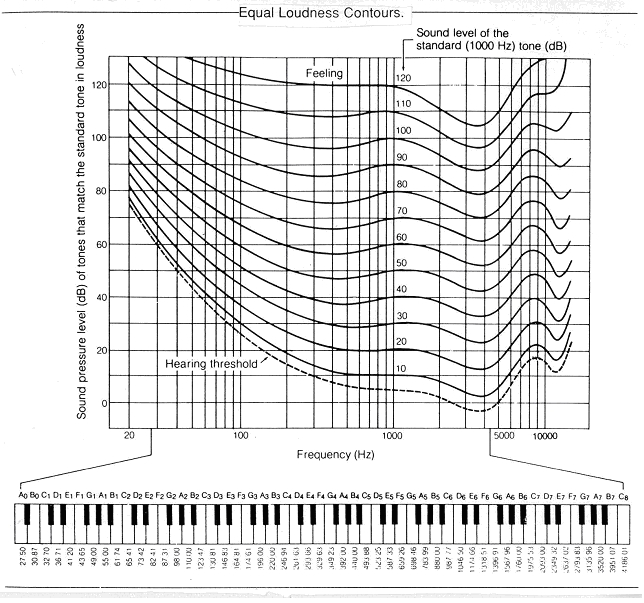

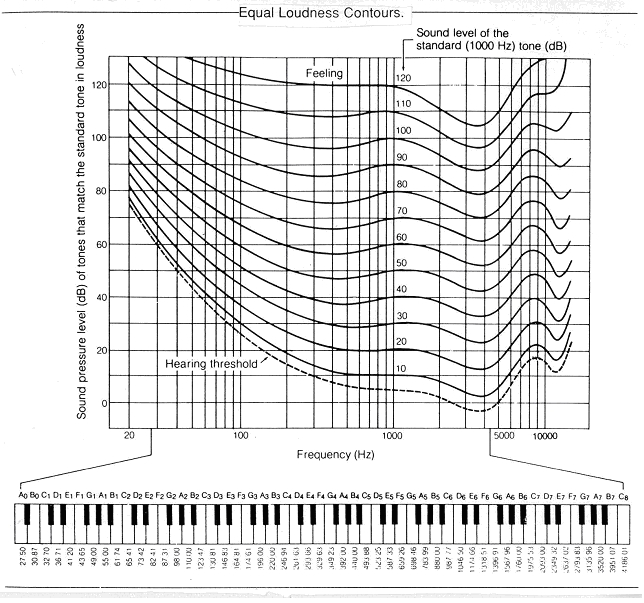

CURVES OF EQUAL PERCEIVED

LOUDNESS FOR dB AND Hz LEVELS

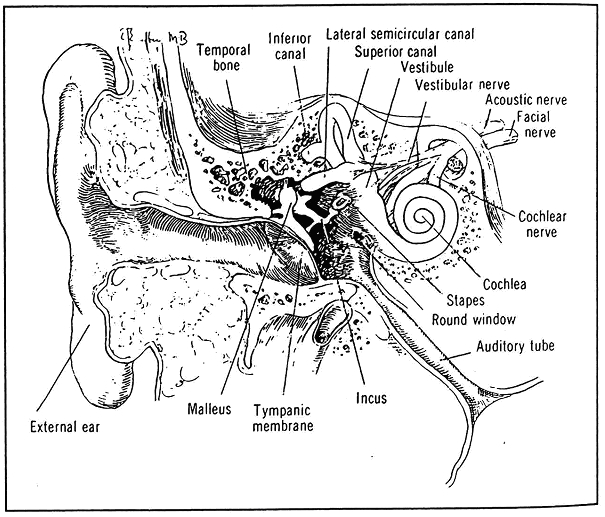

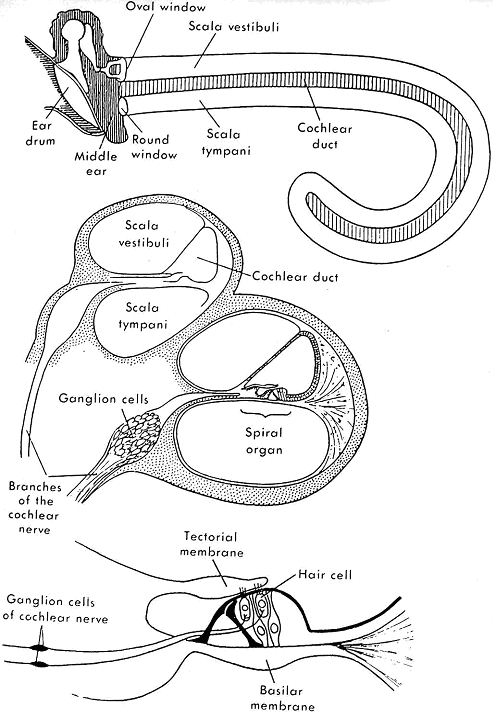

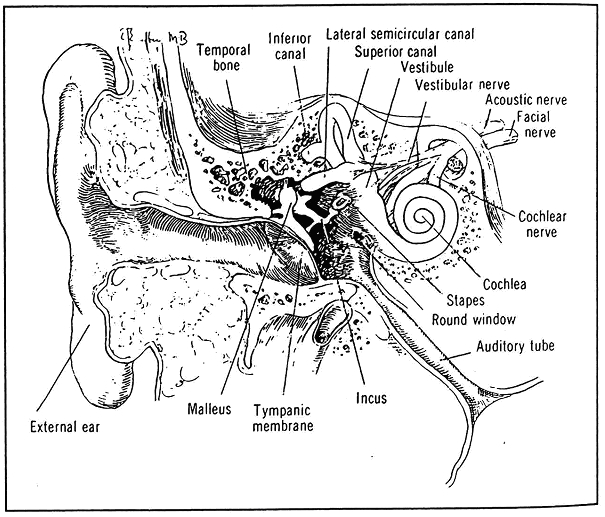

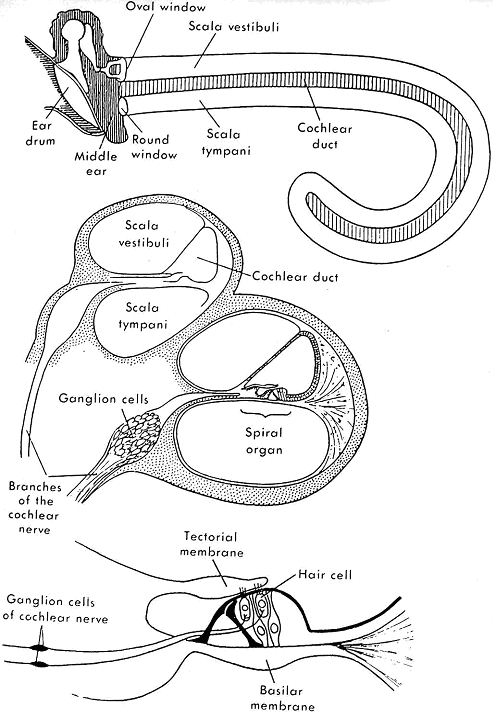

INNER EAR

ON COMMUNICATION FEASIBILITY

{{ folgen spaeter }}

9 Exkurs 2: BEISPIEL FORSCHUNGSPROJEKT

Inhalt:

9.0 Übersicht

9.1 Problemstellung

9.2 Untersuchungsansatz

9.3 Datenerhebung

9.4 Einige Ergebnisse

9.5 Anwendung der Befunde

9.6 Lese-Tips

Eine Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

Rohrmann, B., & Borcherding, K. (1992). Urteils- und Entscheidungsprozesse zur Wohnumwelt. In K. Pawlik & K. H. Stapf (Eds.), Umwelt und Verhalten (217-245). Bern: Huber.

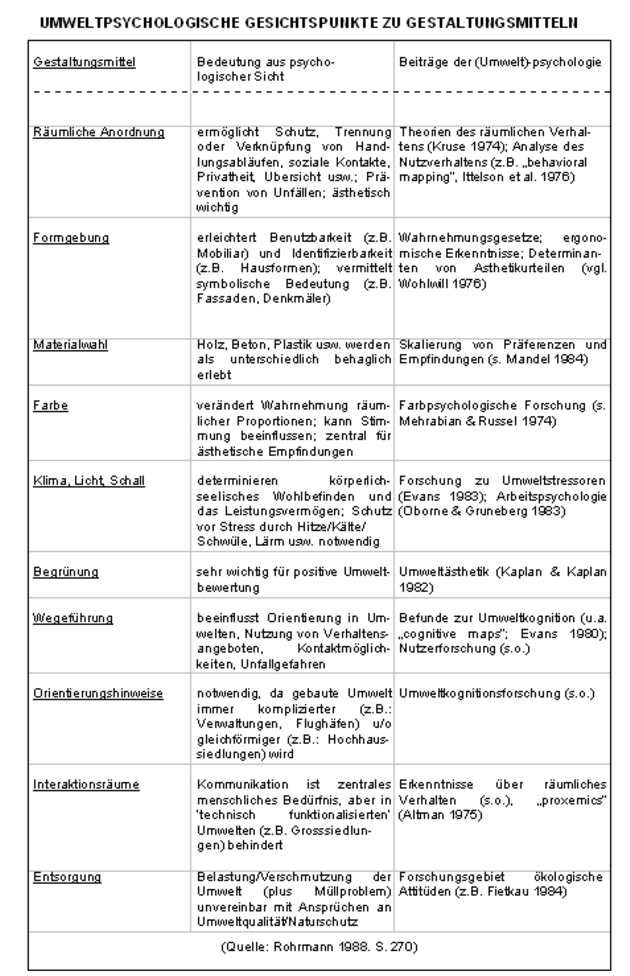

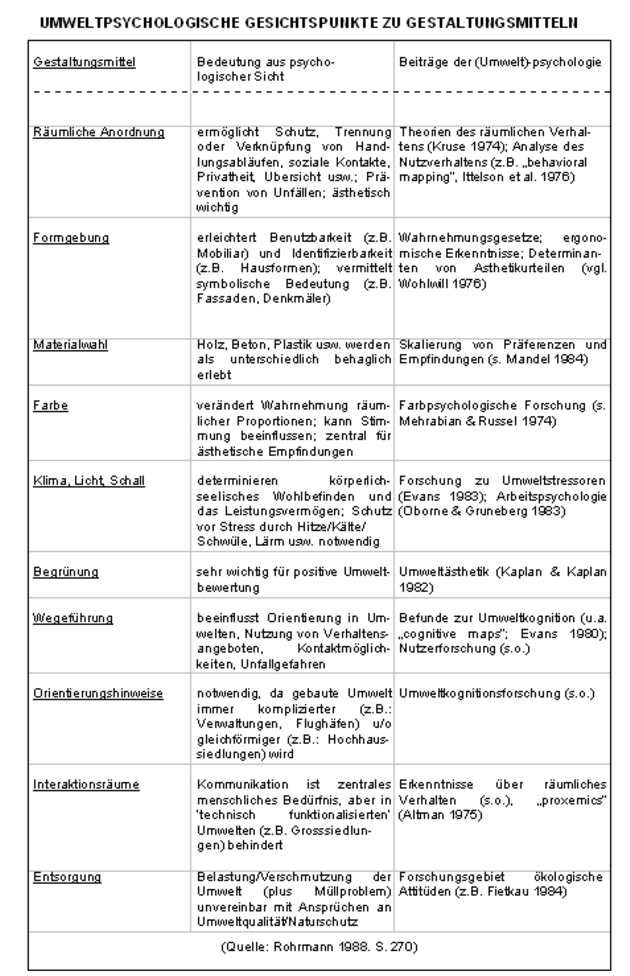

10 GESTALTUNG VON UMWELT

Inhalt:

10.0 Übersicht

10.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

10.2 Zielkriterien

10.3 Angriffspunkte der Umweltgestaltung

10.4 Der Planungsprozess

10.5 Partizipation von Beteiligten

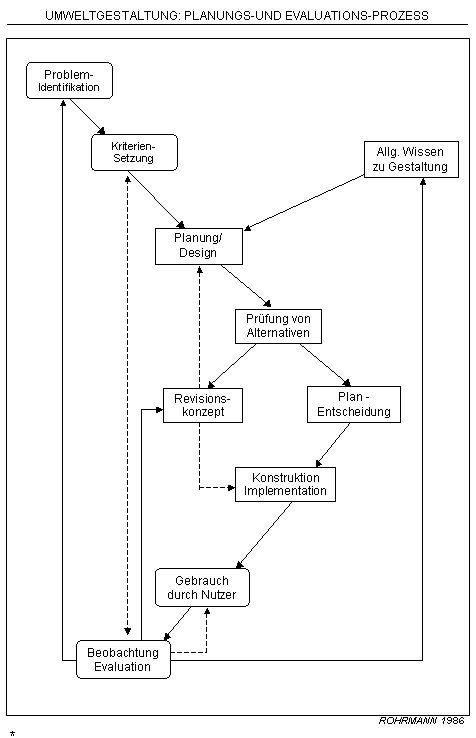

10.6 Lese-Tips

Einige Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

WICHTIGE GESTALTUNGSMITTEL

ZU DENEN UMWELTPSYCHOLOGISCHE EXPERTISE VORLIEGT

Formgebung Materialwahl

Farbe Räumliche Anordnung

Wegeführung Licht, Kilma, Schall, ...

Entsorgung Orientierungshinweise

Interaktionsräume Begrünung

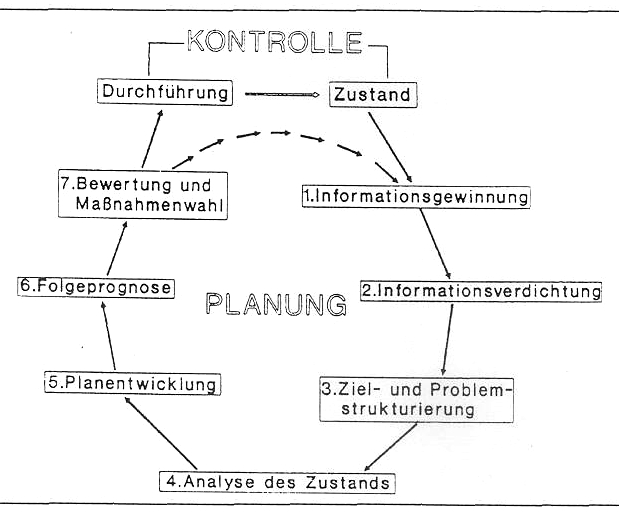

PLANUNGS-MODELL (nach Fischer 1995)

{{ folgen spaeter }}

11 SPEZIELLE BERUFLICHE UND PRIVATE UMWELTEN

Inhalt:

11.0 Übersicht

11.1 Arten baulicher Umwelten

11.2 Wohnungen/Häuser/Siedlungen

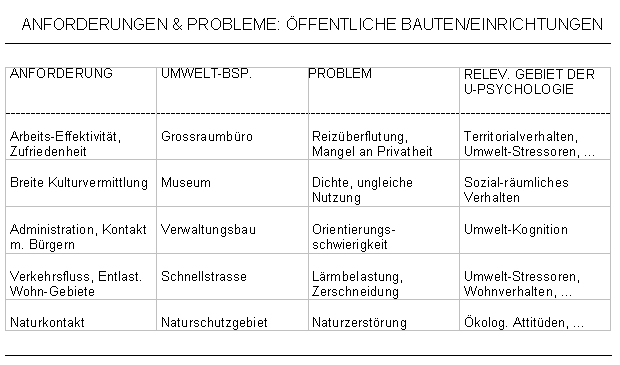

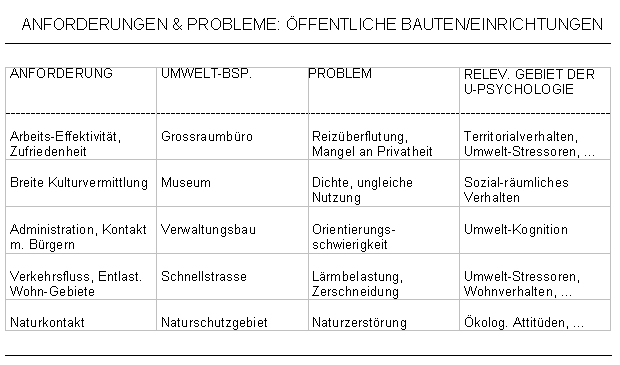

11.3 Anforderungen & Probleme: Öffentliche Bauten

11.4 Natur - Gestaltung und Verwendung

11.5 Sozialwissenschaftliche Lösungsbeiträge

11.6 Lese-Tips

Eine Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

{{ folgen spaeter }}

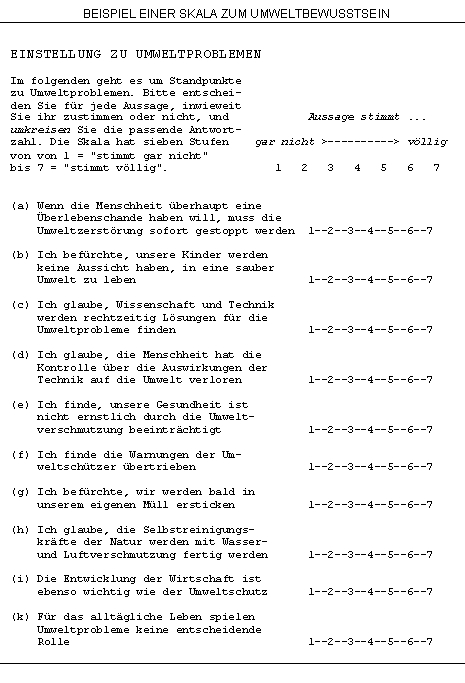

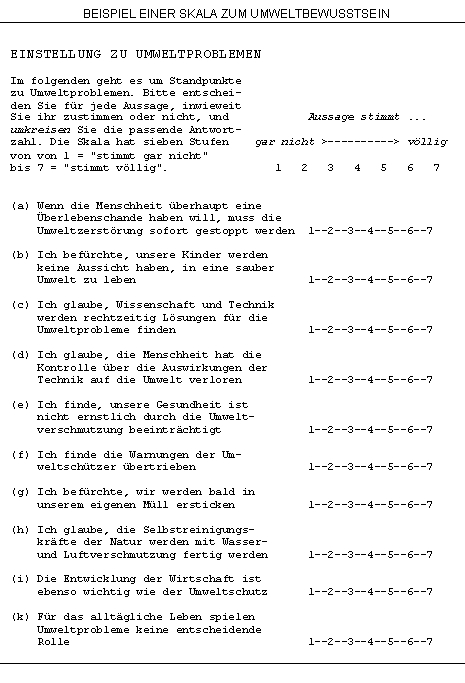

12 ÖKOLOGISCHE ATTITÜDEN

Inhalt:

12.0 Übersicht

12.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

12.2 Dimensionen ökologischer Attitüden

12.3 Beeinflussung von Umweltattitüden

12.4 Lese-Tips

Eine Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

{{ folgen spaeter }}

13 UMWELTSCHUTZVERHALTEN

Inhalt:

13.0 Übersicht

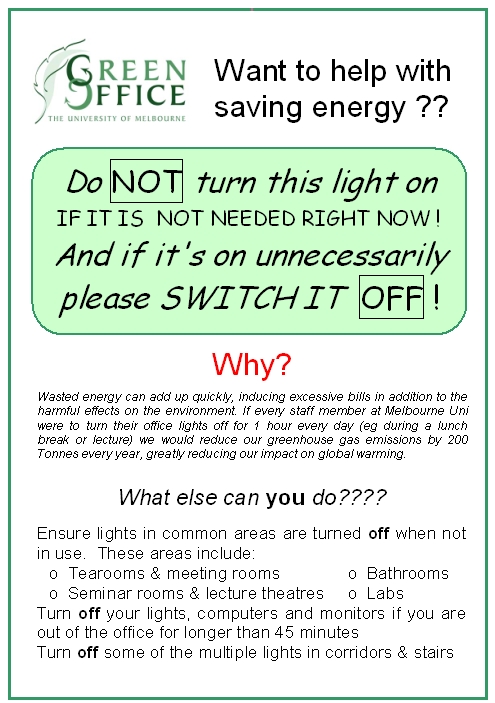

13.1 Bereiche von Umweltverhalten

13.2 Motivierung zu individuellem Umweltschutz

13.3 Gesellschaftlicher Kontext & ökologische Bewegung

13.4 Lese-Tips

Einige Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

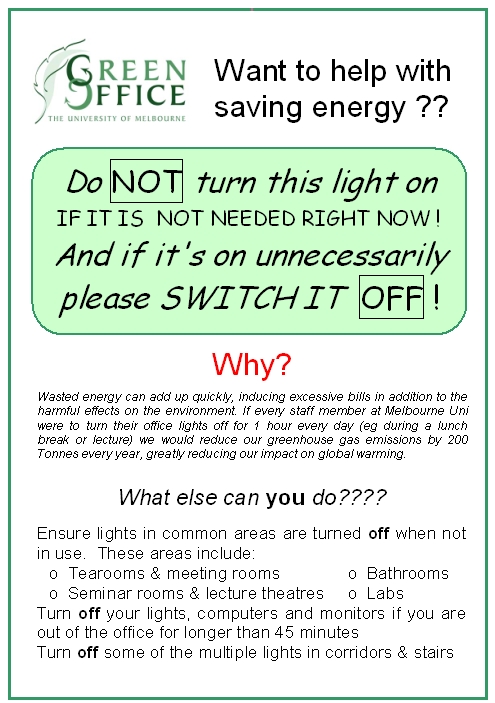

Motivierung zu individuellem Umweltschutz

Einflussfaktoren:

o Attitüden

o Wissen

o Subjektive Wertigkeit

o Gewohnheiten

o Verhaltensanreize

=> reinforcer:

Lob, Geld, Privilegien, Memos, Feedback;

=> model behaviour:

Attraktive und praktische Möglichkeiten, vorhandene Vorbilder, positiver Ausgangszustand

A NOTE ON PRINCIPAL DILEMMAS

IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS

The responsible use of resources has been debated for a long time, yet problem solutions are difficult because of conflicting interests and needs. Such problems can be analyzed in terms of underlying decision dilemmas, as especially social psychologists have pointed out.

For example, the fuels that fill most of our current energy needs (oil, coal, and natural gas) are in short supply and dwindling rapidly. Other resources such as water, trees and metals also will become scarce in the near future if present trends continue. We all know this, yet little changes in our day to day behaviour. Why do people knowingly persist in what is ultimately self-destructive behaviour?

Our inability to manage natural resources efficiently may be traced to what Hardin (1968) called the tragedy of the commons. Originally, the commons referred to public land areas on which anyone could graze livestock with no cost to themselves. The tendency was to exploit the commons by grazing one's sheep on the public land, thereby preserving resources on one's own land. The tragedy lies in the fact that the commons is a limited resource used by individuals acting in there own self-interest. Such a community consumes resources at a rate that endangers the very existence. Such a community consumes resources at a rate that endangers the very existence of the resources itself. The story of the commons is an apt metaphor for all the problems of limited resources that we now face.

The conflict between individual and group interests is called a commons dilemma. It is exacerbated by the tendency to choose immediate rewards even though they have serious long-term costs, which is a decision also referred to as social trap. Dawes (1980) proposed the more general term social dilemma to encompass all these maladaptive, resource-related behaviours.

A valuable elaboration was provided by Vlek & Keren (1992) who systematically analyze types of dilemmas in environmental risk management (influenced by decision theory).

The general problem is the benefit/risk dilemma:

These are situations in which benefits are not available without significant risks. (Problem: the more people are eager to get hold of benefits the more likely will they neglect to appropriately weigh the risks).

Three specific dilemmas are:

Temporal dilemma (or time trap):

Problem: Long-term risks tend to get less weight than immediate benefits.

Social traps:

Problem: Individual interests are often incompatible with societal interests.

Spatial dilemma:

Problem: Decision-makers may not give much weight to risks for groups or nations living elsewhere.

Careless littering or polluting is a good example for what's sometimes called the "individual-good/collective-bad trap" - that is, short-term inconvenience outweighs the long-term benefits of an aesthetically pleasing and healthy environment. (In this case social traps are intertwined with temporal traps).

Most of the empirical research on human behaviour in social dilemmas has been done in the laboratory using simulated games to observe how people manage common resources. Edney's (1979) "Nuts Game" is a good example of such a simulation. In the game, three or more subjects sit around a shallow, nonbreakable, open bowl containing ten hardware hexagonal nuts. Each player's goal is to get as many nuts as possible. Players can take nuts from the bowl at anytime after the game starts, knowing that the experimenter will double the number of nuts remaining in the bowl after each ten-second interval. The game continues until some time limit is reached or the bowl is empty. The wise strategy, of course, is to show restraint - take one or two nuts out during each period, and gradually accumulate a stockpile. Edney reports, however, that about two thirds of the groups never even make it to the first replenishment stage! Usually a greedy frenzy of grabbing instantly destroys what would otherwise be a self-replenishing resource. According to Edney, the nuts in the bowl symbolise any limited resource pool (Whales or oil, for example). In spite of the fact that people know the limits of the resources, social pressures in the situation encourage resource-destructive behaviour.

Source:

The above was compiled by BR, using material from Dawes 1980, McAndrew 1993; Vaughan & Hogg 1995, Vlek & Keren 1992.

A NOTE ON THE COMPLEXITY OF SAVING-THE-ENVIRONMENT ACTIONS

[from Bell et al. 2001, Environmental Psychology, p. 472]

"Actions to "save" the environment often involve trade-offs. Actions with low impact on one segment of the environment often have high impact on another segment. For example, using paper plates to save water costs trees; using washable dishes saves trees but costs water and places a burden on waste treatment facilities. A (controversial) case can actually be made that plastic cups have less impact on the environment than paper cups. The more we wash dishes and diapers, the more we place burdens on wastewater facilities sucha s this one."

{{ folgen spaeter }}

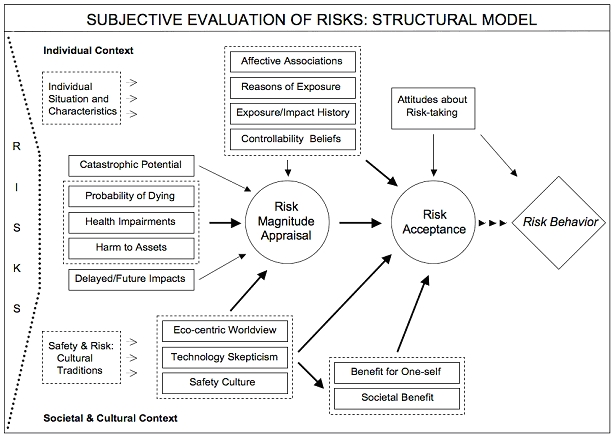

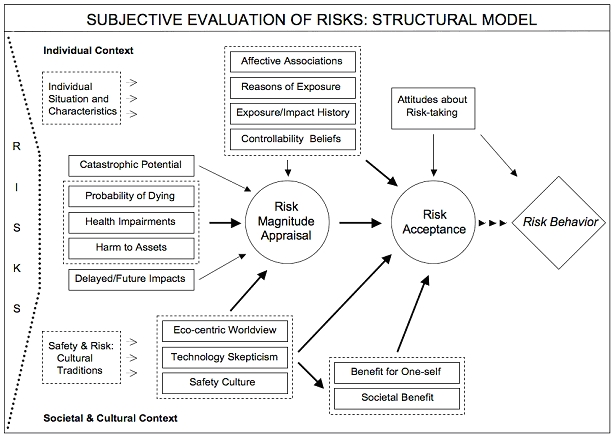

14 Exkurs 3: EINSCHÄTZUNG UMWELTRISIKEN

Inhalt:

14.0 Übersicht

14.1 Forschungsfeld

14.2 Psychologische Ansaetze

14.3 Kognitive Struktur von Risikourteilen

14.4..Risiko-Information und -Kommunikation

14.5 Lese-Tips

Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

Source: Rohrmann 2003

:: For further material about socio-psychological

:: risk research see www.rohrmannresearch.net,

:: click "Project RPX" and "Project RAC" there.

Burton, I., Kates, R.W., White, G. F., (1993). The environment as hazard. New York: Guilford Press.

Jungermann, H., Rohrmann, B., & Wiedemann, P. (1991). Risikokontroversen - Konzepte, Konflikte, Kommunikation. Berlin etc.: Springer.

Rohrmann, B. (1994). Risk perception of different societal groups: Australian findings and cross-national comparisons. Australian Journal of Psychology, 46, 150-163.

Rohrmann, B. (2003). Perception of risk: Research, results, relevance. In J. Gough (Ed.), Sharing the future - Risk communication in practice (pp. 21-44). Christchurch: CAE, University of Canterbury.

Slovic, P. (1992). Perception of risk: Reflections on the psychometric paradigm. In D. Golding & S. Krimsky (Eds.), Theories of risk (117-139). London: Praeger.

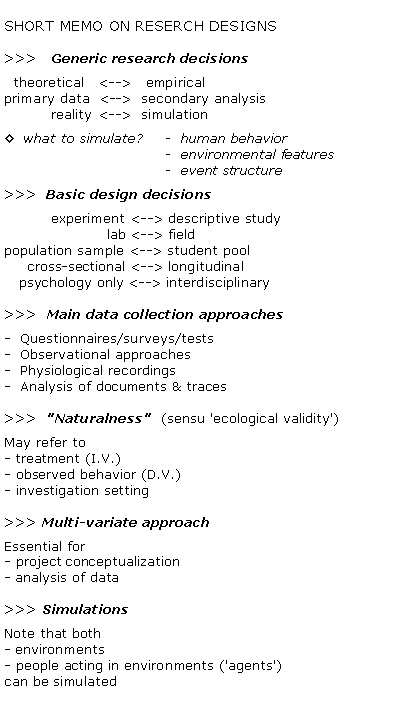

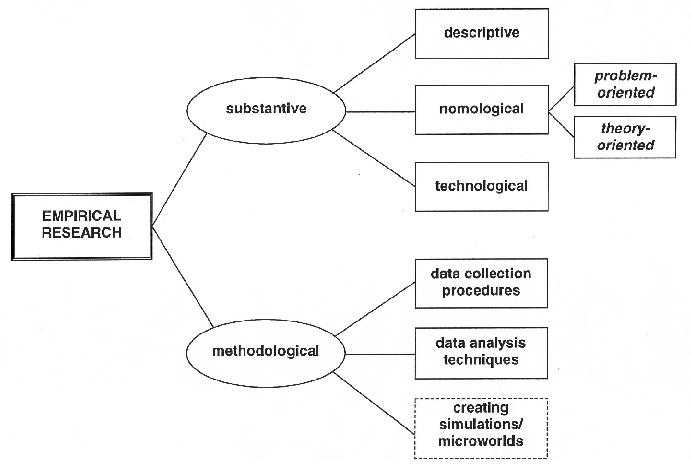

15 METHODIK UMWELTPSYCHOLOGISCHER FORSCHUNG

Inhalt:

15.0 Übersicht

15.1 Relevante Untersuchungsansätze

15.2 Spezielle Datenerhebungsverfahren

15.3 Validität von Befunden

15.4 Lese-Tips

Eine Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

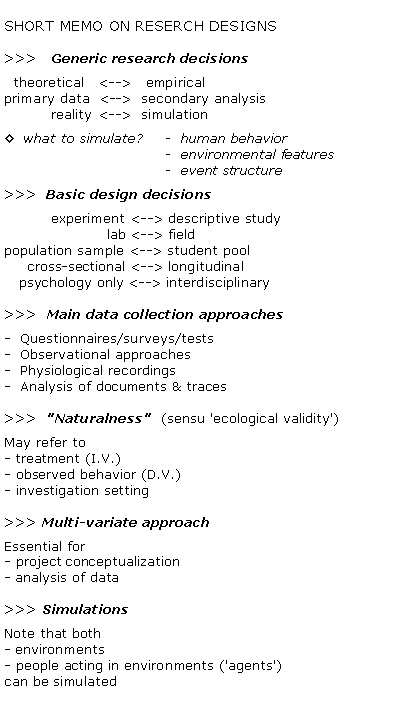

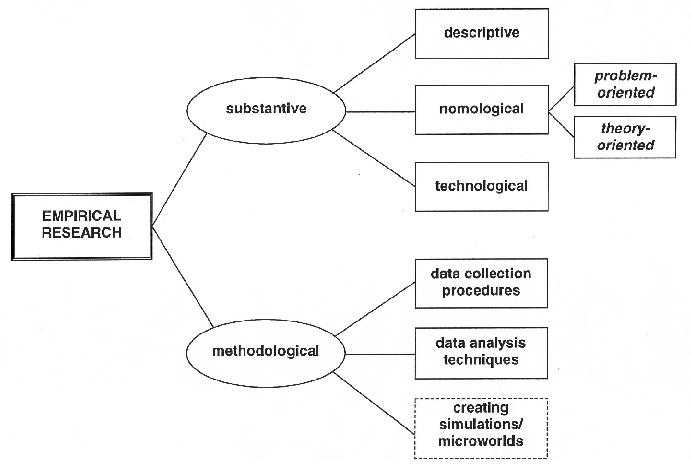

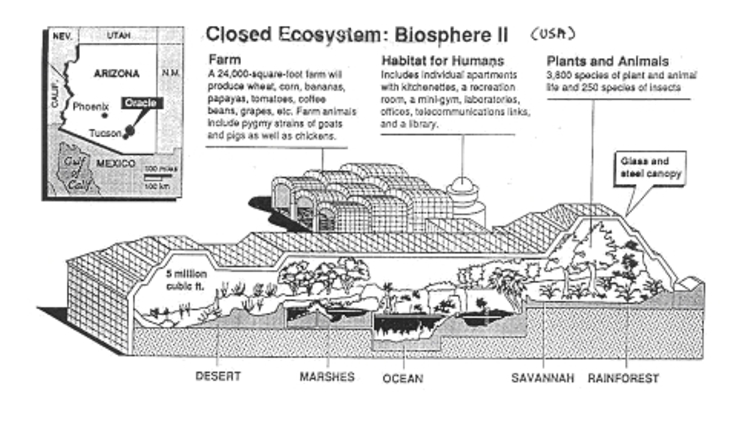

GRAPH re TYPES OF EMPIRICAL RESEARCH (Rohrmann 2000)

Lese-Tips

{{ folgen spaeter }}

16 UMWELT-/ÖKO-PSYCHOLOGIE ALS BERUFSFELD

Inhalt:

16.0 Übersicht

16.1 Erkenntnisbedarf

16.2 Methodologie umweltpsychologischer Expertise

16.3 Anwendung und Anwendbarkeit

16.4 Möglichkeiten beruflicher Tätigkeit

16.5 Lese-Tips

PROBLEMS IN APPLYING ENVIRONMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH

"Environmental Psychology - The essential and challenging discipline" (2003)

The first fundamental truth of environmental psychology is that every human activity occurs in a physical context. Whether one is interested in environmental psychology itself, in another area of psychology, or even in a different discipline, all the action occurs in offices, labs, outdoors, studios, residences, vehicles, institutions, or factories, and all these settings affect everyone's behavior and well‑being. The second fundamental truth is that mutual influence of person and setting usually is neither sudden nor dramatic (certain natural disasters are exceptions). Because these influences are often cumulative and subtle and because we often adapt even to bad settings, they often go unnoticed.

Because of these two truths, the vital importance of person‑environment transactions sometimes is overlooked. But closer inspection of reality and reflection on the previous fifteen chapters forces one to realize that environmental psychology is an essential human endeavor. You may already agree, but it is to remember that not everyone else did, or does.

In its early days, psychology focused on mental dynamics. Later it began to realize the importance of interpersonal and social forces. Except for the lonely voices of a few pioneers, the role played by the physical environment was only recognized 35 years ago. Even today, if your experiences are like mine, you must often field questions about what environmental psychology is. Someone hears that you are studying it and they say, "That sounds interesting. But what is it?" In fact, on this very day, my barber asked me that question! Try to take great care in giving an answer, because the public at large still is generally unaware of this field; its opinion about environmental psychology depends in part on what it hears from you and me.

Of course, you must develop your own assessment of the field to offer the curious. Years of work have convinced me that environmental psychologists have bravely undertaken a task that is ultimately more difficult than that undertaken by any other branch of science. This book never offered to provide simple recipes for solutions to practical problems, and I doubt there are any simple answers to the practical and theoretical problems that environmental psychologists try to solve. Although knowledge is growing so fast that it fairly bulges out of the book, it still provides illumination of theoretical issues and broad research questions more like that offered by the full moon than that offered by the noonday sun.

At this stage, my hope is that readers have learned the real strengths of environmental psychology: having the courage to struggle with complex problems, and refining the methods needed to understand and overcome these problems in local community settings. At present, reading about research and theory in environmental psychology requires more tolerance for uncertainty than a willingness to master a set of established laws. However, the techniques and procedures needed to conduct applied research that can significantly improve the habitability of built and natural settings in your own local community are already well developed and ready for use.

This is all that may reasonably be expected, in my view, after only 35 years of sustained effort. Give us another few decades and resources like those allocated to other areas of science and the growth of understanding of the individual, social and societal processes involved in environmental psychology will compare very favorably with progress in older disciplines. One reason for this lies in the degree of dedication of most environmental psychologists who, in my experience, are even more driven than most others in the knowledge business. They seem to derive extra energy from knowing their work forms an integral part of their everyday life; that they can affect the world around them; that they are always in a physical setting that affects them, is affected by them, and might be improved by their efforts.

>>> Umweltpsychologie

Endgültige Gliederung der Vorlesung von Prof. Rohrmann (2008)

1 DER BEGRIFF UMWELT

1.0 Übersicht

1.1 Begriffsentwicklung und Definitionen

1.2 Arten und Bereiche von Umwelt

1.3 Lese-Tips

2 GEGENSTANDSBESTIMMUNG UMWELT-/ÖKO-PSYCHOLOGIE

2.0 Übersicht

2.1 Etiketten und Definitionen

2.2 Forschungsfelder

2.3 Geschichte der Umwelt-/Ökopsychologie

2.4 Interdisziplinäre Bezüge

2.5 Lese-Tips

3 ÖKOPSYCHOLOGISCHE PERSPEKTIVEN

3.0 Übersicht

3.1 Ökologische Grundbegriffe

3.2 Mensch-Umwelt-Interaktionsmodelle

3.3 Theoretische Ansätze zur Reaktion auf Umweltbedingungen

3.4 Lese-Tips

4 UMWELTKOGNITIONEN

4.0 Übersicht

4.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

4.2 Orientierung in der Umwelt

4.E Exkurs: Erstellung eigener 'cognitive maps'

4.3 Ästhetische Empfindungen

4.4 Bewertung der Umweltqualität

4.5 Lese-Tips

5 RÄUMLICHES UMWELTVERHALTEN

5.0 Übersicht

5.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

5.2 Persönliches Raum- und Distanz-Verhalten

5.3 Effekte räumlicher/sozialer Dichte

5.4 Umzugsverhalten und Wohnungswahl {gekürzt}

5.5 Lese-Tips

6 Exkurs 1: LEHRFILM "KONTAKT UND DISTANZ"

6.0 Einleitung

6.1 F i l m

6.2 Diskussion

7 NUTZUNG VON UMWELTEN

7.0 Übersicht

7.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

7.2 Nutzung und Nutzbarkeit

7.3 Untersuchung von Nutzerverhalten {gekürzt}

7.4 Lese-Tips

8 UMWELTSTRESSOREN UND IHRE AUSWIRKUNGEN

8.0 Übersicht

8.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

8.2 Arten und Auftreten von Umweltstressoren

8.3 Beeinträchtigende Wirkungen

8.4 Bevölkerungsreaktionen {gekürzt}

8.5 Minderungsmaßnahmen

8.6 Lese-Tips

9 Exkurs 2: BEISPIEL EINES FORSCHUNGSPROJEKTES -- Thema: Wohnungswahl

9.4 Einige Ergebnisse {die anderen Abschnitte wurden wegen Zeitmangel gestrichen}

10 GESTALTUNG VON UMWELT

10.0 Übersicht

10.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

10.2 Zielkriterien

10.3 Angriffspunkte der Umweltgestaltung

10.4 Der Planungsprozess

10.5 Partizipation von Beteiligten

10.6 Lese-Tips

11 SPEZIELLE BERUFLICHE UND PRIVATE UMWELTEN

11.0 Übersicht

11.1 Arten baulicher Umwelten

11.2 Wohnungen/Häuser/Siedlungen

11.3 Anforderungen & Probleme: Öffentliche Bauten/Einrichtungen {gekürzt}

11.4 Natur - Gestaltung und Verwendung

11.5 Sozialwissenschaftliche Lösungsbeiträge

11.E Exkurs: Zeichentrickfilm aus Melbourne über klassische Stadtgestaltung

11.6 Lese-Tips

12 ÖKOLOGISCHE ATTITÜDEN

12.0 Übersicht

12.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

12.2 Dimensionen ökologischer Attitüden

12.3 Beeinflussung von Umweltattitüden

12.4 Lese-Tips

13 UMWELTSCHUTZVERHALTEN

13.0 Übersicht

13.1 Bereiche von Umweltverhalten

13.2 Motivierung zu individuellem Umweltschutz

13.3 Gesellschaftlicher/politischer Kontext und ökologische Bewegung {gekürzt}

13.4 Lese-Tips

14 Exkurs 3: EINSCHÄTZUNG UND BEWERTUNG VON UMWELTRISIKEN

14.0 Übersicht

14.1 Forschungsfeld

14.2 Psychologische Ansaetze

14.3 Kognitive Struktur von Risikourteilen

14.4 Risiko-Information und -Kommunikation

14.5 Lese-Tips

15 METHODIK UMWELTPSYCHOLOGISCHER FORSCHUNG

15.0 Übersicht

15.1 Relevante Untersuchungsansätze

15.2 Spezielle Datenerhebungsverfahren {gekürzt}

15.3 Forschung mit Umwelt-Simulationen

15.E Experiment: Evaluation von Computerbildern einer Universitäts-Umwelt

15.4 Validität von Befunden

15.5 Lese-Tips

16 UMWELT-/ÖKO-PSYCHOLOGIE ALS BERUFSFELD

16.0 Übersicht

16.1 Erkenntnisbedarf

16.2 Methodologie umweltpsychologischer Expertise

16.3 Anwendung und Anwendbarkeit

16.4 Möglichkeiten beruflicher Tätigkeit

16.5 Lese-Tips

&& Präsentation des Buchs "DIE STADT" vn Hermann HESSE (1910)

illustriert mit Zeichnungen von Walter SCHMÖGNER

<<< ENDE DER UPI-MATERIALIEN >>>

Inhalt:

1.0 Übersicht

1.1 Begriffsentwicklung und Definitionen

1.2 Arten und Bereiche von Umwelt

1.3 Lese-Tips

Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

natuerliche \ ¦

physische < > Objekte oder Emissionen ¦ Wohn-U

/ gebaute / ¦ Arbeits-U

Umwelt ¦ Verkehrs-U

\ Individuen (Nachbarn) ¦ Freizeit-U

soziale < ¦ Versorgungs-U

Gruppe/Masse ¦

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Lese-Tips

{{ folgen spaeter }}

2 GEGENSTANDSBESTIMMUNG UMWELT-/ÖKO-PSY

Inhalt:

2.0 Übersicht

2.1 Etiketten und Definitionen

2.2 Forschungsfelder

2.3 Geschichte der Ökopsychologie

2.4 Interdisziplinäre Bezüge

2.5 Lese-Tips

Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

Lese-Tips

{{ folgen spaeter }}

3 ÖKOPSYCHOLOGISCHE PERSPEKTIVEN

Inhalt:

3.0 Übersicht

3.1 Ökologische Grundbegriffe

3.2 Mensch-Umwelt-Interaktionsmodelle

3.3 Theoretische Ansätze

3.4 Lese-Tips

Einige Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

{{ folgen spaeter }}

4 UMWELTKOGNITIONEN

Inhalt:

4.0 Übersicht

4.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

4.2 Orientierung in der Umwelt

4.3 Ästhetische Empfindungen

4.4 Bewertung der Umweltqualität

4.5 Lese-Tips

Einige Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

BRUNSWIK'S "LENS MODEL" OF ENVIRONMENTAL PERCEPTION

EIN TEXT ZUR "MOND-ILLUSION

Moon sliver, wider than a mile - Why does the moon appear different sizes?

By Sandra Blaksee <New York Times>

One of the most familiar illusions embraced by the human brain has finally been solved, say a father-son pair of scientists who were armed with a contraption than projects fake moons onto the sky.

In the "moon illusion", the moon rising or setting over the horizon appears much bigger than the moon directly overhead, even though both of the moons are the same size. By allowing viewers to move simulated moons towards and away from each other, the scientists demonstrate that the so-called moon illusion seems to be caused by the brain's inability to estimate huge distances in the empty night sky. The brain has many similar perceptual difficulties, they said, which produce a variety of convincing optical illusions.

An article explaining the moon illusion appears in the 4 January issue of Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, written by Dr. Lloyd Kaufman, a professor emeritus of psychology from New York University, and Dr. James Kaufman, a physicist at IMB's Almaden Research Centre in San Jose, California.

The Kaufmans said the moon illusion had baffled scientists since antiquity. Aristotle, Ptolemy, Leonardo da Vinci, Johannes Kepler, Rene Descartes and many others had tried to explain it. But now, scientists are able to take advantage of modern insights into the nature of human perception. After an image falls on the retina, where it resembles the image on a camera lens, it is sent into the brain for further processing. Within the brain's serpentine circuitry, every two-dimensional image is converted into a richer, more accurate three-dimensional representation of the world. It was within these many processing steps that illusions were born, the scientists said.

"If you look at a photograph of a person stretched out in front of you on the grass, you see enormous feet and a tiny head," Dr. Lloyd Kaufman said. But the brain took that same image and made all sorts of so-called size constancy corrections so that the person did not look distorted. The visual "fact" that the person's body was not misshapen was actually an illusion. Given the understanding that the human brain constantly deals in illusions, two theories have emerged to explain the moon illusion. They are based on opposing views of how the perceptual system computes size and distance.

One theory attributes the moon illusion to how the brain deals with the apparent size of distant objects. Because of how the light falls on the retina, and other details, the brain judges the moon to be smaller than it really is, and thus father away, when it is viewed in empty space.

The second theory holds that the moon illusion arises from how the brain deals with apparent distance not size. When people view the moon on the horizon, the story goes, their brains use myriad signals from foreground terrain to compute the moon's size. Even in flat terrain, the horizon appears very far away, so any large object seen there, like a mountain must be enormous.

Thus the moon is treated like a mountain - Huge and very far away. But when people look straight up at the moon, they no longer have land clues to compute distances. Their brains- and not their eyes - fail to adjust to the enormous distance involved and perceive the moon as being closer and closer as it rises into the night sky. The brain interprets this apparent distance discrepancy to mean that the overhead moon is much smaller than it is.

To find out which theory is correct, the Kaufmans invented a way to measure how people perceive distances to the moon. Virtually all other experiments had dealt with how people perceived the size of the moon, the Kaufmans said.

Their device consists of a laptop computer, a mirror and two lenses that can project luminous discs, or simulated moons, into the cloudless daytime sky. The apparatus works like a stereogram. Double images are directed into each eye, where they fuse somewhere inside the brain, giving the illusion of depth.

Dr Lloyd Kaufman took five people to a hillside and had them look through the apparatus until they saw two identical moons side by side. One was a fixed moon that they could hold steady. The other was a reference moon that they could move forward and back in space. People were asked to position the reference moon so it was halfway between themselves and fixed moon, the Kaufmans said.

When moving the reference moon in relation to a fixed moon on the horizon, people place the reference moon about 33 metres from themselves, the scientists said. But, when they moved the reference moon in relation to an overhead moon, they placed it only eight metres away. Thus, the "halfway" point to a horizon moon was four times father away than the halfway point to an overhead moon.

In a second experiment, subjects looked at two moons projected high overhead and pressing a key, moved one closer to themselves. They were startled to find that as the moving moon got closer, it always appeared to be getting smaller and smaller, not bigger.

The two experiments confirm the second theory, the Kaufmans said. If the brain were attending to size, the closer-in moon should appear larger, but it did not.

Source: New York Times; cited from The Age, 24-01-00

TEXT ZU MOND-PHASEN UND VERHALTEN

A Recycled Cycle: Moon Phases and Behaviour

Folklore and commonly held beliefs maintain that many aspects of our behaviour are related to phases of the moon. Sexual prowess, menstrual cycles, birthrates, death rates, suicide rates, homicide rates, and hospital admission rates are among the phenomena various people claim are affected by the moon. Often, it is maintained that a full moon increases strange behaviour. Surveys of undergraduates indicate that half of them believe people behave strangely when the moon is full (Rotton & Kelly, 1995a). Other beliefs are that the tidal pulls of full and new moons influence human physiology or psychic functioning, or that the moon's perigee (closest distance to the Earth) and apogee (farthest distance from the Earth) influence us in strange ways. Indeed, the word lunacy is derived from a belief in a relationship between the moon and mental illness.

The last full moon of the previous millennium occurred on December 22, 1999, which also corresponded to its perigee, as well as to the winter solstice or shortest day in the Northern Hemisphere. In addition, the moon on that date was almost as close to the sun as it ever gets. As a result, it appeared 14% larger than at its apogee as well as 7% brighter. No particular anomalies in human behaviour were reported. But the lore says that when a similar full moon, perigee, and solstice occurred on December 20 and 21, 1866, the Sioux warrior Crazy Horse was inspired to ambush and wipe out 80 U.S. soldiers (Golden, 1999).

It is the case that lunar tides affect some marine organisms, and there is some evidence a full moon ever so slightly increases temperatures on Earth (by 0.02° K; Balling & Cerveny, 1995). From time to time, research also appears that actually gives credence to beliefs that the moon causes drastic changes in human behaviour. For example, Blackman and Catalina (1973) found that full moons were associated with an increase in the number of patients visiting a psychiatric emergency room. In another study, Lieber and Sherin (1972) reported a relationship between moon phase and homicide. Rape, robbery, and assault; burglary, larceny, and theft; and auto theft, drunkenness, disorderly conduct, and attacks on family and children have also been linked to a full moon (Tasso & Miller, 1976). At first glance, then, it would appear that science has confirmed the folklore of the ancients (see also Garzino, 1982).

Not so fast! Closer examination of the data indicates that the mysticism of the lunar cycle may be more myth than reality. Campbell (1982), Kelly, Rotton, and Culver (1985-86), and Rotton and Kelly (1985b, 1987), among others, have reviewed the available research on the topic and concluded that no firm relationship exists between any lunar variable and human behaviour (see also Byrnes & Kelly, 1992). For example, studies conducted over a period of three to five years may report a relationship between the full moon and suicide or homicide for only one of the years studied. Researchers who conclude that such a relationship exists are ignoring the fact that it does not exist for the other years, or that these behaviours are actually lower during full moons for another year. Moreover, it is consistently found that crimes increase on weekends. For some periods of the year, lunar phases may coincide with weekends. Data based on only these periods will obviously show a relationship between the moon and crime, but data based on other periods will show the opposite relationship or no relationship at all. In addition, a self-fulfilling prophecy may operate: If police believe crime increases during a full moon, they may become more vigilant at these times and thus arrest more people. Altogether, the evidence suggests that positive links between moon phases and behaviour are spurious and are attributable to mere chance probabilities in the data or to variables not considered by individual investigators. Why do these mistaken beliefs persist? Reasons include misconceptions about physical processes (Culver, Rotton, & Kelly, 1988), attitudes acquired from one's peers (Rotton, Kelly, & Elortegui, 1986), and cognitive biases, such as basing conclusions on only a few occurrences. Given the tenacity of beliefs in moon phases causing disruptive behaviour, we suspect the lunacy of it all will continue for some time!

Source: Bell, P.A., Greene, T.C., Fisher, J.D., & Baum, A. (2001).

Environmental Psychology. Orlando, FL: Harcourt .

{{ folgen spaeter }}

5 RÄUMLICHES UMWELTVERHALTEN

Inhalt:

5.0 Übersicht

5.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

5.2 Persönliches Raum- und Distanz-Verhalten

5.3 Effekte räumlicher/sozialer Dichte

5.4 Umzugsverhalten und Wohnungswahl

5.5 Lese-Tips

Einige Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

DAS ENTSCHEIDUNGSPROBLEM "UMZUG"

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

> Entscheidungen:

o Bleiben oder Umziehen?

o {falls Umzug:} Wechsel von Wohnung/Haus/Ortsteil/Stadt/Region/Land?

> Prozesse bei der Wohnungswahl

o Suchen

o Besichtigen

o Bewerten

o Wählen

> Umziehen = räumliches Verhalten auf Makro-Ebene

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

=> Vgl. Modell in Materialien zu Kap. 9 !

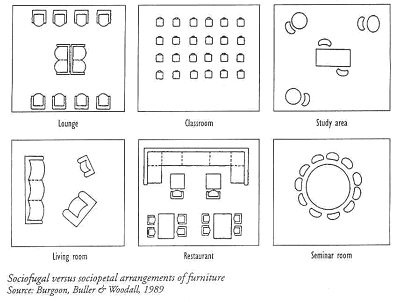

CONTACT & INTERACTION ZONES

{{ folgen spaeter }}

6 Exkurs 1: LEHRFILM "KONTAKT UND DISTANZ"

Inhalt:

6.0 Einleitung

6.1 F i l m

6.2 Diskussion

Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

:: This film was made at Frankfurt University

:: many years ago - - yet it is still instructive

:: for lectures in Environmental Psychology

Lese-Tips

Autoren: PREISER & WANNENMACHER 1980

7 NUTZUNG VON UMWELTEN

Inhalt:

7.0 Übersicht

7.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

7.2 Nutzung und Nutzbarkeit

7.3 Untersuchung von Nutzerverhalten

7.4 Lese-Tips

Eine Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

NUTZER-ZIELE, NUTZUNGSVERHALTEN, NUTZBARKEIT

Relevante Aktivitaetsbereiche

o Arbeiten o Wohnen o Erholen

Nutzerverhalten

o Sich orientieren o Aktivitäten durchführen o Umwelt verändern

Nutzbarkeits-Aspekte:

o Funktionalität o Raumbedarf o Ortswechsel

Untersuchung von Nutzerverhalten

Analyse des raum-zeitl. Verhaltens:

o Orte Zeiten o Wege

Methodik:

o Beobachten o Befragen

{{ folgen spaeter }}

8 UMWELTSTRESSOREN UND IHRE AUSWIRKUNGEN

Inhalt:

8.0 Übersicht

8.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

8.2 Arten und Auftreten von Umweltstressoren

8.3 Beeinträchtigende Wirkungen

8.4 Bevölkerungsreaktionen

8.5 Minderungsmaßnahmen

8.6 Lese-Tips

Einige Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

DECIBEL[A] SCALE AND NOISE EXAMPLES

INNER EAR

ON COMMUNICATION FEASIBILITY

{{ folgen spaeter }}

9 Exkurs 2: BEISPIEL FORSCHUNGSPROJEKT

Inhalt:

9.0 Übersicht

9.1 Problemstellung

9.2 Untersuchungsansatz

9.3 Datenerhebung

9.4 Einige Ergebnisse

9.5 Anwendung der Befunde

9.6 Lese-Tips

Eine Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

Rohrmann, B., & Borcherding, K. (1992). Urteils- und Entscheidungsprozesse zur Wohnumwelt. In K. Pawlik & K. H. Stapf (Eds.), Umwelt und Verhalten (217-245). Bern: Huber.

10 GESTALTUNG VON UMWELT

Inhalt:

10.0 Übersicht

10.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

10.2 Zielkriterien

10.3 Angriffspunkte der Umweltgestaltung

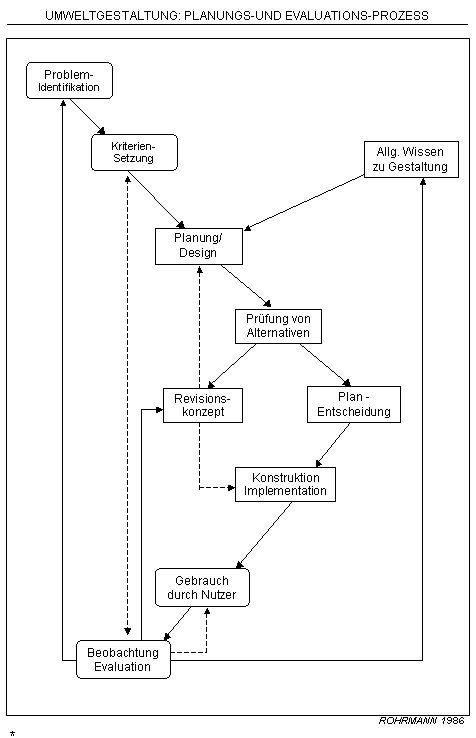

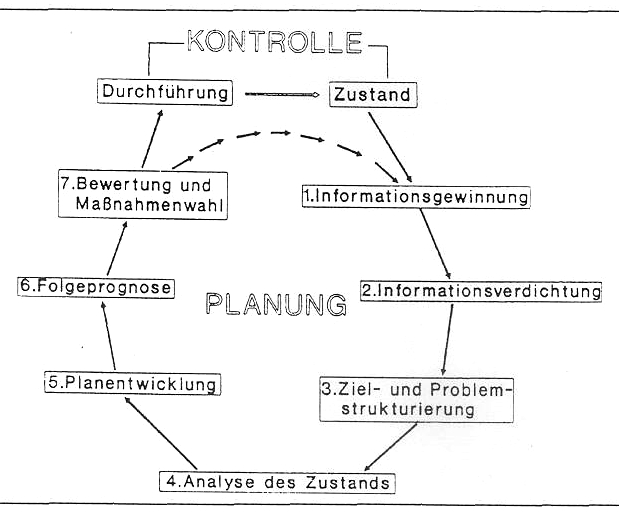

10.4 Der Planungsprozess

10.5 Partizipation von Beteiligten

10.6 Lese-Tips

Einige Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

WICHTIGE GESTALTUNGSMITTEL

ZU DENEN UMWELTPSYCHOLOGISCHE EXPERTISE VORLIEGT

Formgebung Materialwahl

Farbe Räumliche Anordnung

Wegeführung Licht, Kilma, Schall, ...

Entsorgung Orientierungshinweise

Interaktionsräume Begrünung

PLANUNGS-MODELL (nach Fischer 1995)

{{ folgen spaeter }}

11 SPEZIELLE BERUFLICHE UND PRIVATE UMWELTEN

Inhalt:

11.0 Übersicht

11.1 Arten baulicher Umwelten

11.2 Wohnungen/Häuser/Siedlungen

11.3 Anforderungen & Probleme: Öffentliche Bauten

11.4 Natur - Gestaltung und Verwendung

11.5 Sozialwissenschaftliche Lösungsbeiträge

11.6 Lese-Tips

Eine Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

{{ folgen spaeter }}

12 ÖKOLOGISCHE ATTITÜDEN

Inhalt:

12.0 Übersicht

12.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

12.2 Dimensionen ökologischer Attitüden

12.3 Beeinflussung von Umweltattitüden

12.4 Lese-Tips

Eine Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

{{ folgen spaeter }}

13 UMWELTSCHUTZVERHALTEN

Inhalt:

13.0 Übersicht

13.1 Bereiche von Umweltverhalten

13.2 Motivierung zu individuellem Umweltschutz

13.3 Gesellschaftlicher Kontext & ökologische Bewegung

13.4 Lese-Tips

Einige Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

Motivierung zu individuellem Umweltschutz

Einflussfaktoren:

o Attitüden

o Wissen

o Subjektive Wertigkeit

o Gewohnheiten

o Verhaltensanreize

=> reinforcer:

Lob, Geld, Privilegien, Memos, Feedback;

=> model behaviour:

Attraktive und praktische Möglichkeiten, vorhandene Vorbilder, positiver Ausgangszustand

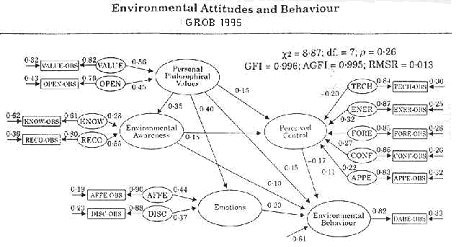

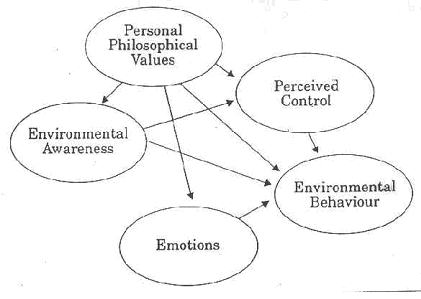

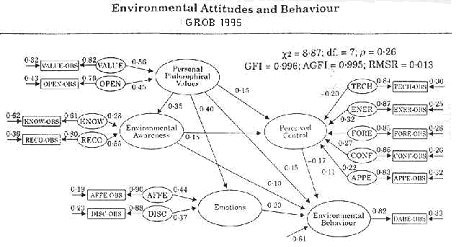

GROB (1995):

THEORETICAL MODEL OF ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIOR

OF ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIOR

A NOTE ON PRINCIPAL DILEMMAS

IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS

The responsible use of resources has been debated for a long time, yet problem solutions are difficult because of conflicting interests and needs. Such problems can be analyzed in terms of underlying decision dilemmas, as especially social psychologists have pointed out.

For example, the fuels that fill most of our current energy needs (oil, coal, and natural gas) are in short supply and dwindling rapidly. Other resources such as water, trees and metals also will become scarce in the near future if present trends continue. We all know this, yet little changes in our day to day behaviour. Why do people knowingly persist in what is ultimately self-destructive behaviour?

Our inability to manage natural resources efficiently may be traced to what Hardin (1968) called the tragedy of the commons. Originally, the commons referred to public land areas on which anyone could graze livestock with no cost to themselves. The tendency was to exploit the commons by grazing one's sheep on the public land, thereby preserving resources on one's own land. The tragedy lies in the fact that the commons is a limited resource used by individuals acting in there own self-interest. Such a community consumes resources at a rate that endangers the very existence. Such a community consumes resources at a rate that endangers the very existence of the resources itself. The story of the commons is an apt metaphor for all the problems of limited resources that we now face.

The conflict between individual and group interests is called a commons dilemma. It is exacerbated by the tendency to choose immediate rewards even though they have serious long-term costs, which is a decision also referred to as social trap. Dawes (1980) proposed the more general term social dilemma to encompass all these maladaptive, resource-related behaviours.

A valuable elaboration was provided by Vlek & Keren (1992) who systematically analyze types of dilemmas in environmental risk management (influenced by decision theory).

The general problem is the benefit/risk dilemma:

These are situations in which benefits are not available without significant risks. (Problem: the more people are eager to get hold of benefits the more likely will they neglect to appropriately weigh the risks).

Three specific dilemmas are:

Temporal dilemma (or time trap):

Problem: Long-term risks tend to get less weight than immediate benefits.

Social traps:

Problem: Individual interests are often incompatible with societal interests.

Spatial dilemma:

Problem: Decision-makers may not give much weight to risks for groups or nations living elsewhere.

Careless littering or polluting is a good example for what's sometimes called the "individual-good/collective-bad trap" - that is, short-term inconvenience outweighs the long-term benefits of an aesthetically pleasing and healthy environment. (In this case social traps are intertwined with temporal traps).

Most of the empirical research on human behaviour in social dilemmas has been done in the laboratory using simulated games to observe how people manage common resources. Edney's (1979) "Nuts Game" is a good example of such a simulation. In the game, three or more subjects sit around a shallow, nonbreakable, open bowl containing ten hardware hexagonal nuts. Each player's goal is to get as many nuts as possible. Players can take nuts from the bowl at anytime after the game starts, knowing that the experimenter will double the number of nuts remaining in the bowl after each ten-second interval. The game continues until some time limit is reached or the bowl is empty. The wise strategy, of course, is to show restraint - take one or two nuts out during each period, and gradually accumulate a stockpile. Edney reports, however, that about two thirds of the groups never even make it to the first replenishment stage! Usually a greedy frenzy of grabbing instantly destroys what would otherwise be a self-replenishing resource. According to Edney, the nuts in the bowl symbolise any limited resource pool (Whales or oil, for example). In spite of the fact that people know the limits of the resources, social pressures in the situation encourage resource-destructive behaviour.

Source:

The above was compiled by BR, using material from Dawes 1980, McAndrew 1993; Vaughan & Hogg 1995, Vlek & Keren 1992.

A NOTE ON THE COMPLEXITY OF SAVING-THE-ENVIRONMENT ACTIONS

[from Bell et al. 2001, Environmental Psychology, p. 472]

"Actions to "save" the environment often involve trade-offs. Actions with low impact on one segment of the environment often have high impact on another segment. For example, using paper plates to save water costs trees; using washable dishes saves trees but costs water and places a burden on waste treatment facilities. A (controversial) case can actually be made that plastic cups have less impact on the environment than paper cups. The more we wash dishes and diapers, the more we place burdens on wastewater facilities sucha s this one."

{{ folgen spaeter }}

14 Exkurs 3: EINSCHÄTZUNG UMWELTRISIKEN

Inhalt:

14.0 Übersicht

14.1 Forschungsfeld

14.2 Psychologische Ansaetze

14.3 Kognitive Struktur von Risikourteilen

14.4..Risiko-Information und -Kommunikation

14.5 Lese-Tips

Info-Boxen zu diesem Kapitel:

Source: Rohrmann 2003

:: For further material about socio-psychological

:: risk research see www.rohrmannresearch.net,

:: click "Project RPX" and "Project RAC" there.

Burton, I., Kates, R.W., White, G. F., (1993). The environment as hazard. New York: Guilford Press.

Jungermann, H., Rohrmann, B., & Wiedemann, P. (1991). Risikokontroversen - Konzepte, Konflikte, Kommunikation. Berlin etc.: Springer.

Rohrmann, B. (1994). Risk perception of different societal groups: Australian findings and cross-national comparisons. Australian Journal of Psychology, 46, 150-163.

Rohrmann, B. (2003). Perception of risk: Research, results, relevance. In J. Gough (Ed.), Sharing the future - Risk communication in practice (pp. 21-44). Christchurch: CAE, University of Canterbury.

Slovic, P. (1992). Perception of risk: Reflections on the psychometric paradigm. In D. Golding & S. Krimsky (Eds.), Theories of risk (117-139). London: Praeger.

15 METHODIK UMWELTPSYCHOLOGISCHER FORSCHUNG

Inhalt:

15.0 Übersicht

15.1 Relevante Untersuchungsansätze

15.2 Spezielle Datenerhebungsverfahren

15.3 Validität von Befunden

15.4 Lese-Tips

Eine Info-Box zu diesem Kapitel:

GRAPH re TYPES OF EMPIRICAL RESEARCH (Rohrmann 2000)

Lese-Tips

{{ folgen spaeter }}

16 UMWELT-/ÖKO-PSYCHOLOGIE ALS BERUFSFELD

Inhalt:

16.0 Übersicht

16.1 Erkenntnisbedarf

16.2 Methodologie umweltpsychologischer Expertise

16.3 Anwendung und Anwendbarkeit

16.4 Möglichkeiten beruflicher Tätigkeit

16.5 Lese-Tips

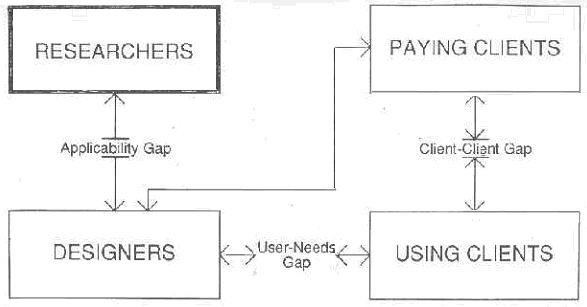

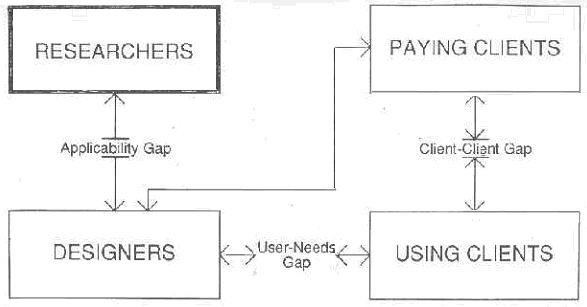

PROBLEMS IN APPLYING ENVIRONMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH

ACADEMIC RESEARCHERS - DIFFICULTIES

IN BEING PRACTICAL?

"Environmental Psychology - The essential and challenging discipline" (2003)

The first fundamental truth of environmental psychology is that every human activity occurs in a physical context. Whether one is interested in environmental psychology itself, in another area of psychology, or even in a different discipline, all the action occurs in offices, labs, outdoors, studios, residences, vehicles, institutions, or factories, and all these settings affect everyone's behavior and well‑being. The second fundamental truth is that mutual influence of person and setting usually is neither sudden nor dramatic (certain natural disasters are exceptions). Because these influences are often cumulative and subtle and because we often adapt even to bad settings, they often go unnoticed.

Because of these two truths, the vital importance of person‑environment transactions sometimes is overlooked. But closer inspection of reality and reflection on the previous fifteen chapters forces one to realize that environmental psychology is an essential human endeavor. You may already agree, but it is to remember that not everyone else did, or does.

In its early days, psychology focused on mental dynamics. Later it began to realize the importance of interpersonal and social forces. Except for the lonely voices of a few pioneers, the role played by the physical environment was only recognized 35 years ago. Even today, if your experiences are like mine, you must often field questions about what environmental psychology is. Someone hears that you are studying it and they say, "That sounds interesting. But what is it?" In fact, on this very day, my barber asked me that question! Try to take great care in giving an answer, because the public at large still is generally unaware of this field; its opinion about environmental psychology depends in part on what it hears from you and me.

Of course, you must develop your own assessment of the field to offer the curious. Years of work have convinced me that environmental psychologists have bravely undertaken a task that is ultimately more difficult than that undertaken by any other branch of science. This book never offered to provide simple recipes for solutions to practical problems, and I doubt there are any simple answers to the practical and theoretical problems that environmental psychologists try to solve. Although knowledge is growing so fast that it fairly bulges out of the book, it still provides illumination of theoretical issues and broad research questions more like that offered by the full moon than that offered by the noonday sun.

At this stage, my hope is that readers have learned the real strengths of environmental psychology: having the courage to struggle with complex problems, and refining the methods needed to understand and overcome these problems in local community settings. At present, reading about research and theory in environmental psychology requires more tolerance for uncertainty than a willingness to master a set of established laws. However, the techniques and procedures needed to conduct applied research that can significantly improve the habitability of built and natural settings in your own local community are already well developed and ready for use.

This is all that may reasonably be expected, in my view, after only 35 years of sustained effort. Give us another few decades and resources like those allocated to other areas of science and the growth of understanding of the individual, social and societal processes involved in environmental psychology will compare very favorably with progress in older disciplines. One reason for this lies in the degree of dedication of most environmental psychologists who, in my experience, are even more driven than most others in the knowledge business. They seem to derive extra energy from knowing their work forms an integral part of their everyday life; that they can affect the world around them; that they are always in a physical setting that affects them, is affected by them, and might be improved by their efforts.

Lese-Tips

{{ folgen spaeter }}

>>> Umweltpsychologie

Endgültige Gliederung der Vorlesung von Prof. Rohrmann (2008)

1 DER BEGRIFF UMWELT

1.0 Übersicht

1.1 Begriffsentwicklung und Definitionen

1.2 Arten und Bereiche von Umwelt

1.3 Lese-Tips

2 GEGENSTANDSBESTIMMUNG UMWELT-/ÖKO-PSYCHOLOGIE

2.0 Übersicht

2.1 Etiketten und Definitionen

2.2 Forschungsfelder

2.3 Geschichte der Umwelt-/Ökopsychologie

2.4 Interdisziplinäre Bezüge

2.5 Lese-Tips

3 ÖKOPSYCHOLOGISCHE PERSPEKTIVEN

3.0 Übersicht

3.1 Ökologische Grundbegriffe

3.2 Mensch-Umwelt-Interaktionsmodelle

3.3 Theoretische Ansätze zur Reaktion auf Umweltbedingungen

3.4 Lese-Tips

4 UMWELTKOGNITIONEN

4.0 Übersicht

4.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

4.2 Orientierung in der Umwelt

4.E Exkurs: Erstellung eigener 'cognitive maps'

4.3 Ästhetische Empfindungen

4.4 Bewertung der Umweltqualität

4.5 Lese-Tips

5 RÄUMLICHES UMWELTVERHALTEN

5.0 Übersicht

5.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

5.2 Persönliches Raum- und Distanz-Verhalten

5.3 Effekte räumlicher/sozialer Dichte

5.4 Umzugsverhalten und Wohnungswahl {gekürzt}

5.5 Lese-Tips

6 Exkurs 1: LEHRFILM "KONTAKT UND DISTANZ"

6.0 Einleitung

6.1 F i l m

6.2 Diskussion

7 NUTZUNG VON UMWELTEN

7.0 Übersicht

7.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

7.2 Nutzung und Nutzbarkeit

7.3 Untersuchung von Nutzerverhalten {gekürzt}

7.4 Lese-Tips

8 UMWELTSTRESSOREN UND IHRE AUSWIRKUNGEN

8.0 Übersicht

8.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

8.2 Arten und Auftreten von Umweltstressoren

8.3 Beeinträchtigende Wirkungen

8.4 Bevölkerungsreaktionen {gekürzt}

8.5 Minderungsmaßnahmen

8.6 Lese-Tips

9 Exkurs 2: BEISPIEL EINES FORSCHUNGSPROJEKTES -- Thema: Wohnungswahl

9.4 Einige Ergebnisse {die anderen Abschnitte wurden wegen Zeitmangel gestrichen}

10 GESTALTUNG VON UMWELT

10.0 Übersicht

10.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

10.2 Zielkriterien

10.3 Angriffspunkte der Umweltgestaltung

10.4 Der Planungsprozess

10.5 Partizipation von Beteiligten

10.6 Lese-Tips

11 SPEZIELLE BERUFLICHE UND PRIVATE UMWELTEN

11.0 Übersicht

11.1 Arten baulicher Umwelten

11.2 Wohnungen/Häuser/Siedlungen

11.3 Anforderungen & Probleme: Öffentliche Bauten/Einrichtungen {gekürzt}

11.4 Natur - Gestaltung und Verwendung

11.5 Sozialwissenschaftliche Lösungsbeiträge

11.E Exkurs: Zeichentrickfilm aus Melbourne über klassische Stadtgestaltung

11.6 Lese-Tips

12 ÖKOLOGISCHE ATTITÜDEN

12.0 Übersicht

12.1 Wesentliche Begriffe

12.2 Dimensionen ökologischer Attitüden

12.3 Beeinflussung von Umweltattitüden

12.4 Lese-Tips

13 UMWELTSCHUTZVERHALTEN

13.0 Übersicht

13.1 Bereiche von Umweltverhalten

13.2 Motivierung zu individuellem Umweltschutz

13.3 Gesellschaftlicher/politischer Kontext und ökologische Bewegung {gekürzt}

13.4 Lese-Tips

14 Exkurs 3: EINSCHÄTZUNG UND BEWERTUNG VON UMWELTRISIKEN

14.0 Übersicht

14.1 Forschungsfeld

14.2 Psychologische Ansaetze

14.3 Kognitive Struktur von Risikourteilen

14.4 Risiko-Information und -Kommunikation

14.5 Lese-Tips

15 METHODIK UMWELTPSYCHOLOGISCHER FORSCHUNG

15.0 Übersicht

15.1 Relevante Untersuchungsansätze

15.2 Spezielle Datenerhebungsverfahren {gekürzt}

15.3 Forschung mit Umwelt-Simulationen

15.E Experiment: Evaluation von Computerbildern einer Universitäts-Umwelt

15.4 Validität von Befunden

15.5 Lese-Tips

16 UMWELT-/ÖKO-PSYCHOLOGIE ALS BERUFSFELD

16.0 Übersicht

16.1 Erkenntnisbedarf

16.2 Methodologie umweltpsychologischer Expertise

16.3 Anwendung und Anwendbarkeit

16.4 Möglichkeiten beruflicher Tätigkeit

16.5 Lese-Tips

&& Präsentation des Buchs "DIE STADT" vn Hermann HESSE (1910)

illustriert mit Zeichnungen von Walter SCHMÖGNER

<<< ENDE DER UPI-MATERIALIEN >>>